Struggling with your portraits? You might find my E-book helpful. Click here

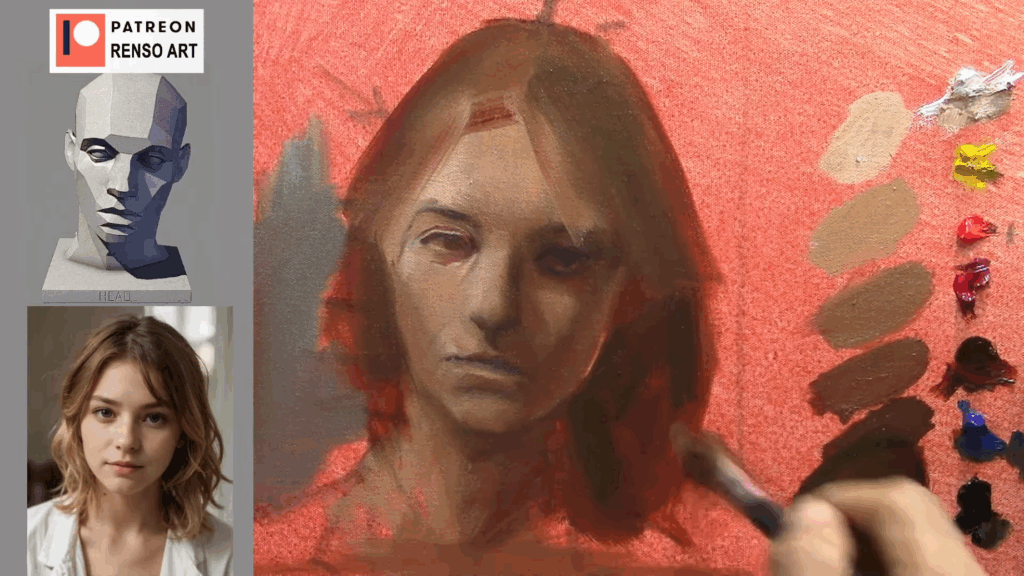

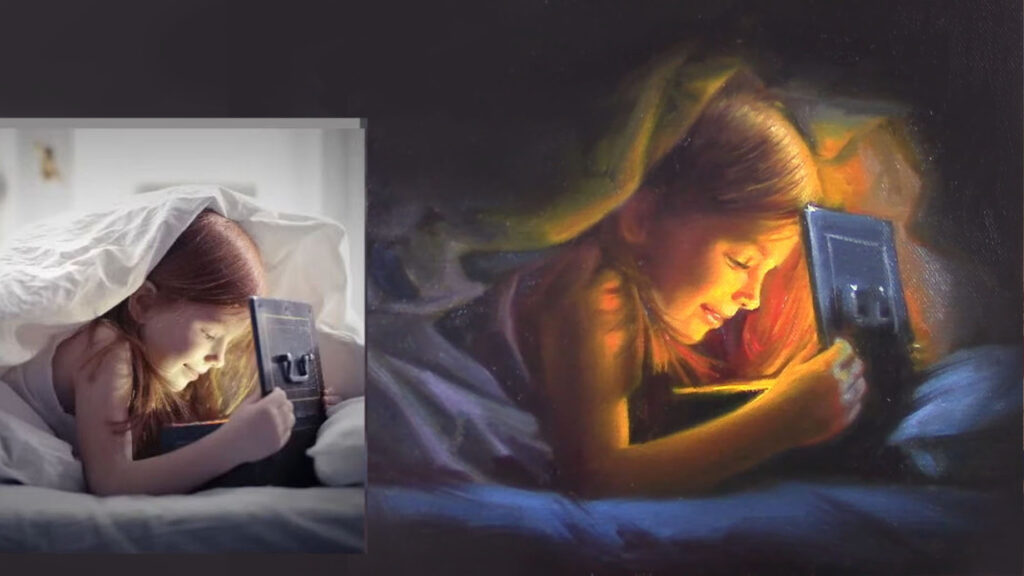

Bring depth, light, and life to your portraits through color awareness.

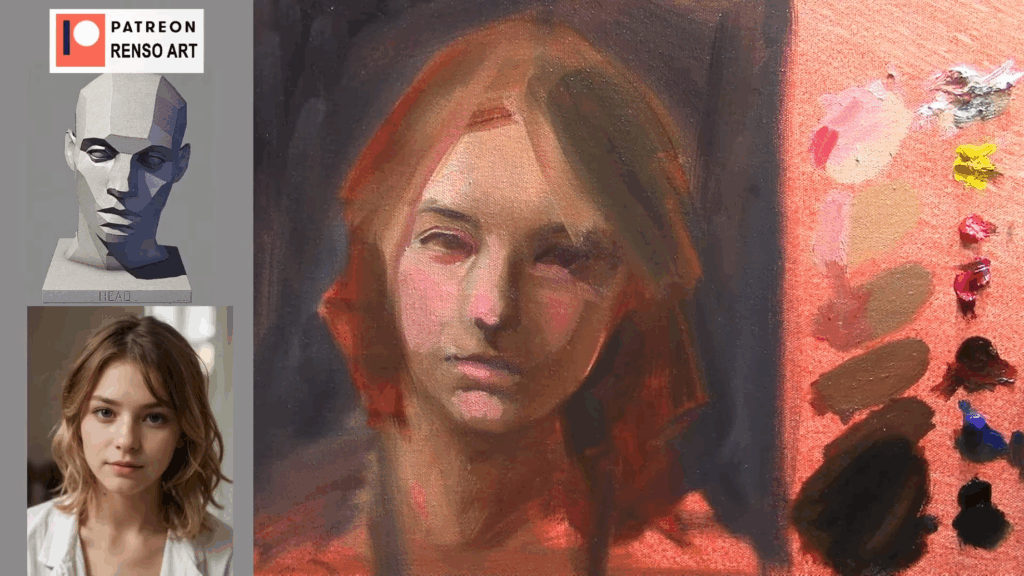

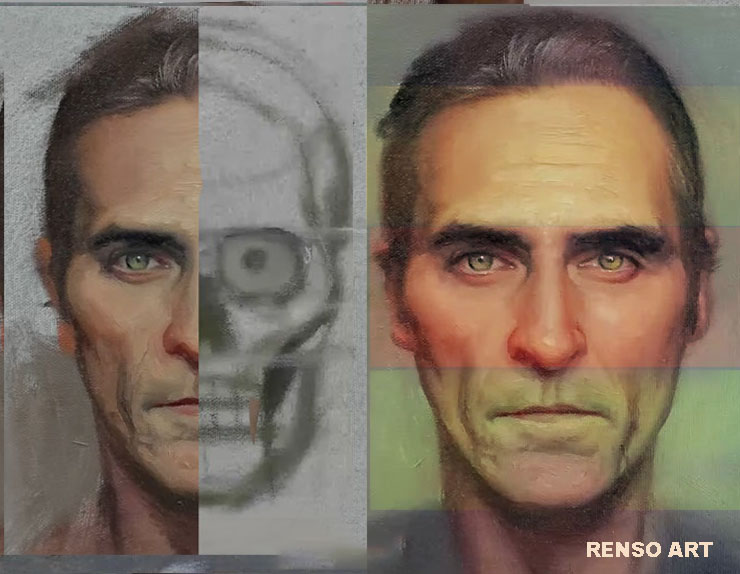

I remember my first portraits were pretty light. Even though I liked some of them, the reason they didn’t feel complete was that they lacked contrast, my shadows weren’t dark enough, and the colors were too muted. I can’t blame my teachers, though; I clearly remember one of them repeating over and over where to place the colors on the face. But back then, my main goal was to capture the likeness and include as many details as possible.

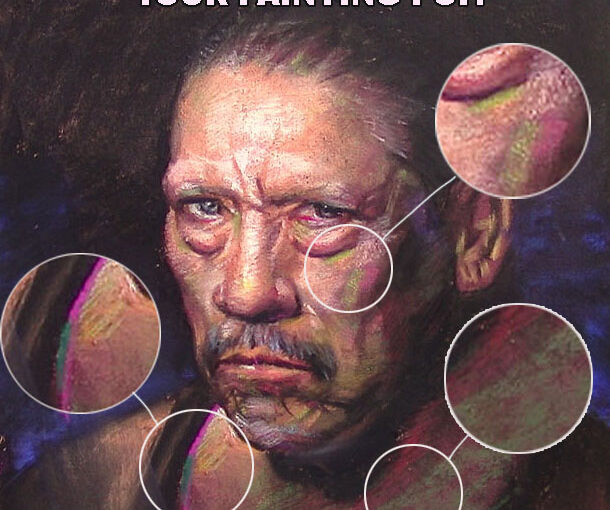

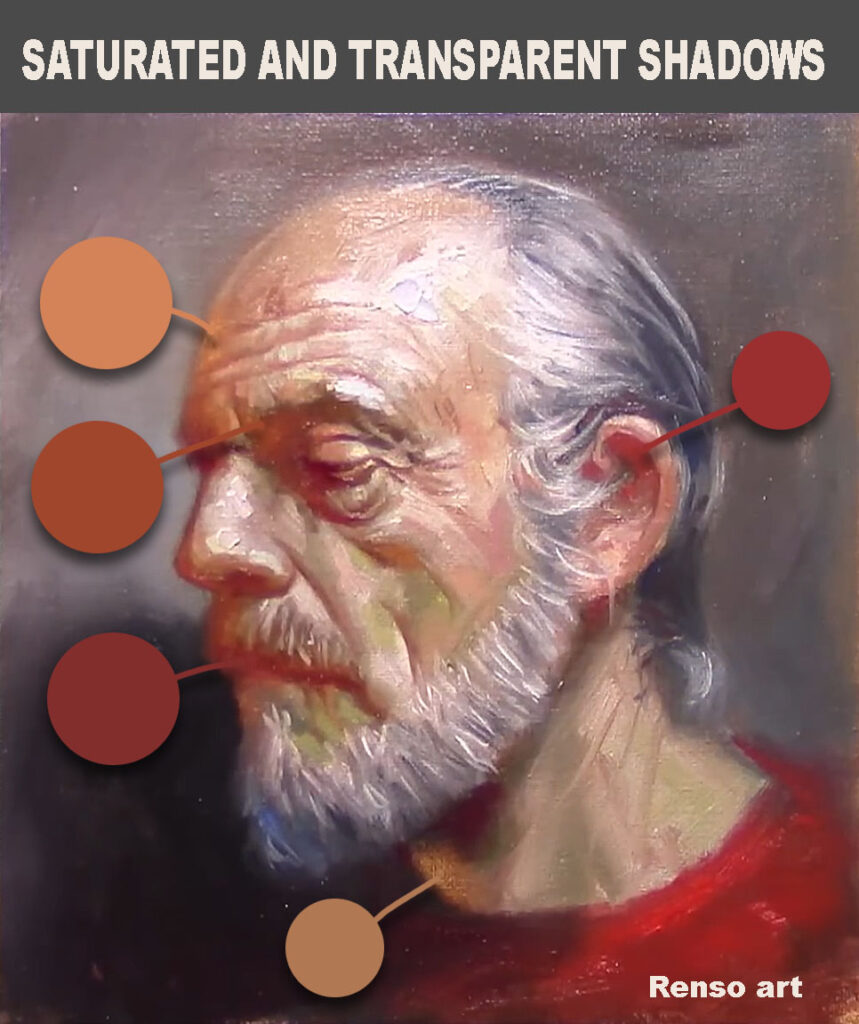

Here’s my advice: don’t repeat my mistakes. Make sure your shadows are dark enough, and don’t be afraid to add more color to the face. Why are we so hesitant? In my case, I was afraid of making the shadows too dark or the colors too bright—I didn’t want the painting to look like a clown. But the sooner you embrace that challenge, the faster you’ll improve.

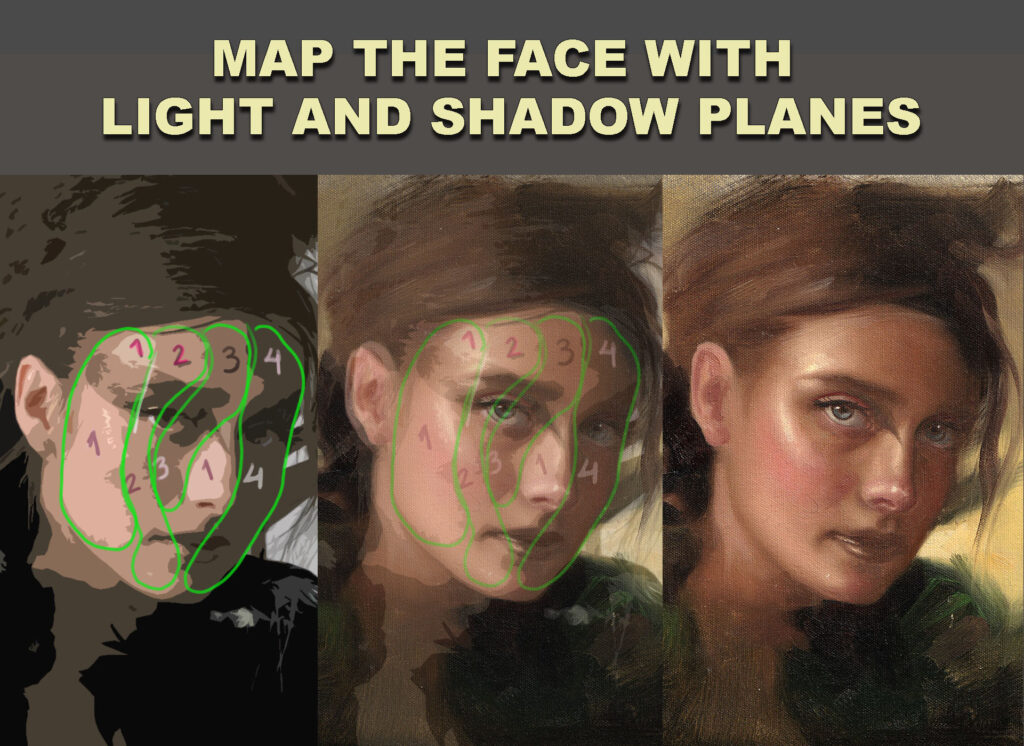

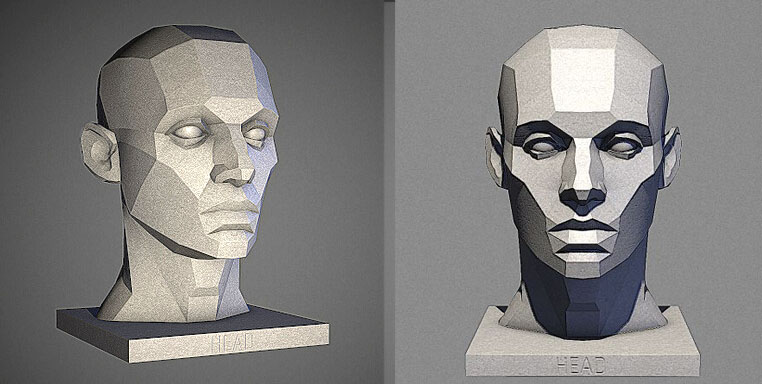

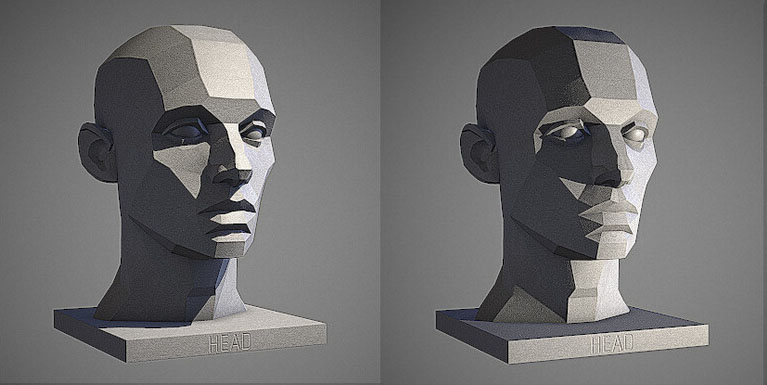

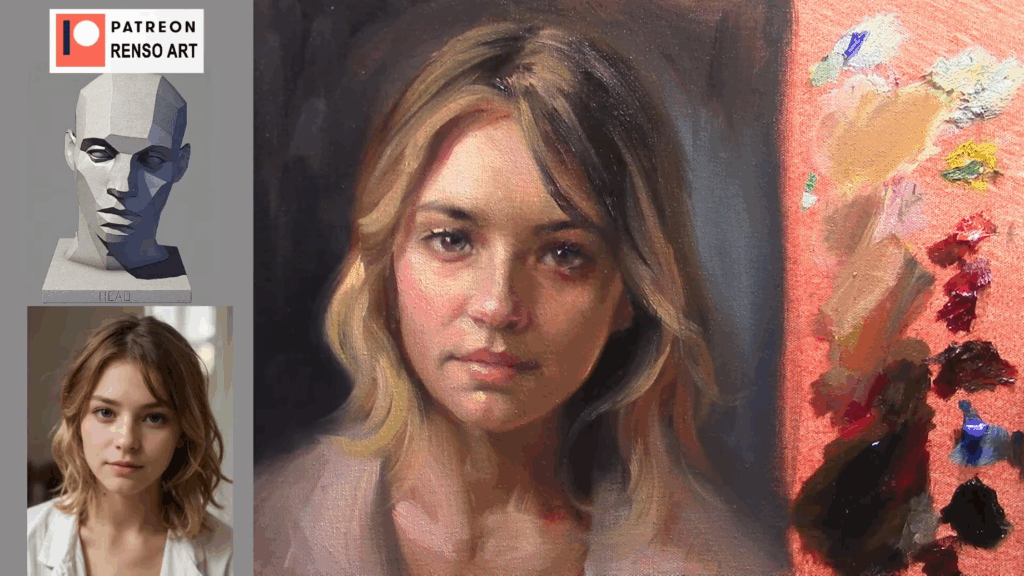

One essential concept in portrait painting is understanding the color planes of the face: how light interacts with the form, and how subtle color shifts define structure, mood, and realism.

🎨 What Are Color Planes?

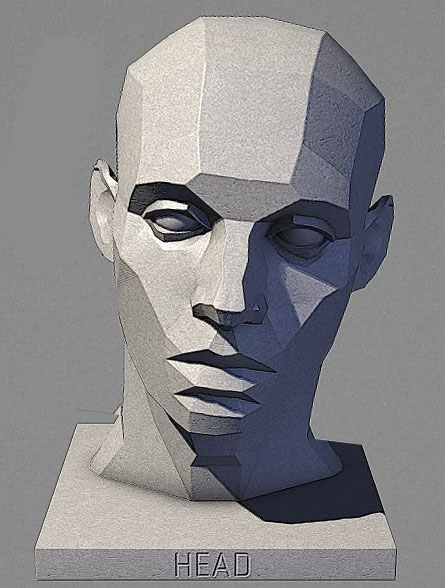

The human face isn’t flat. It’s made of angled surfaces (planes) that catch light differently depending on their direction. Each of these planes reflects light—and thus color—uniquely. By recognizing and painting these variations, you can create a more believable, dimensional face rather than a flat or overly blended one.

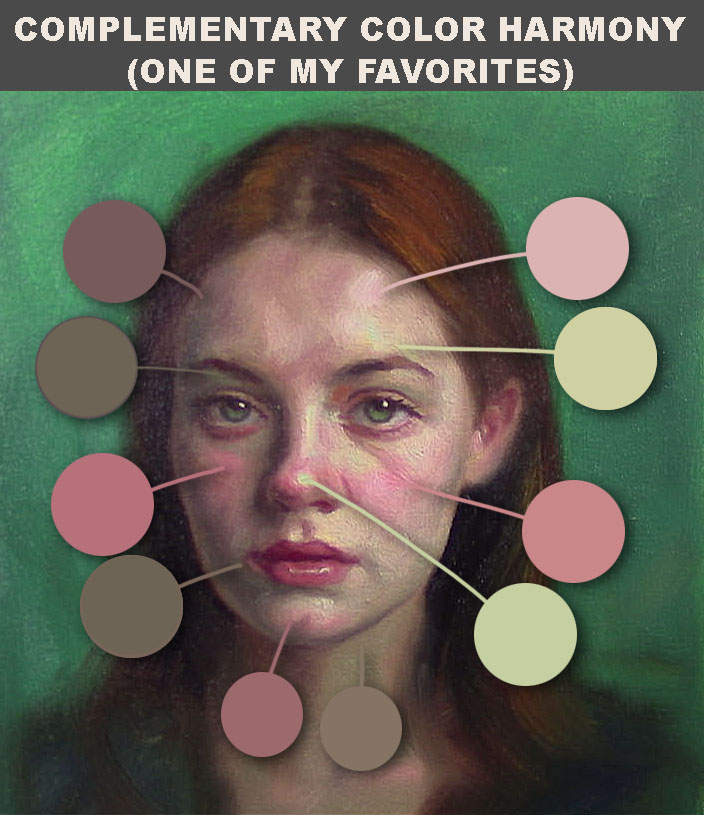

🔺 Key Facial Planes and Their Color Tendencies

- Frontal Planes (Forehead, Cheeks, Chin)

These areas often face the light directly and tend to reflect cooler and lighter tones, especially in natural light. You’ll often see a mix of soft pinks, peach, and neutral skin tones here. - Side Planes (Temples, Sides of the Nose, Jaw)

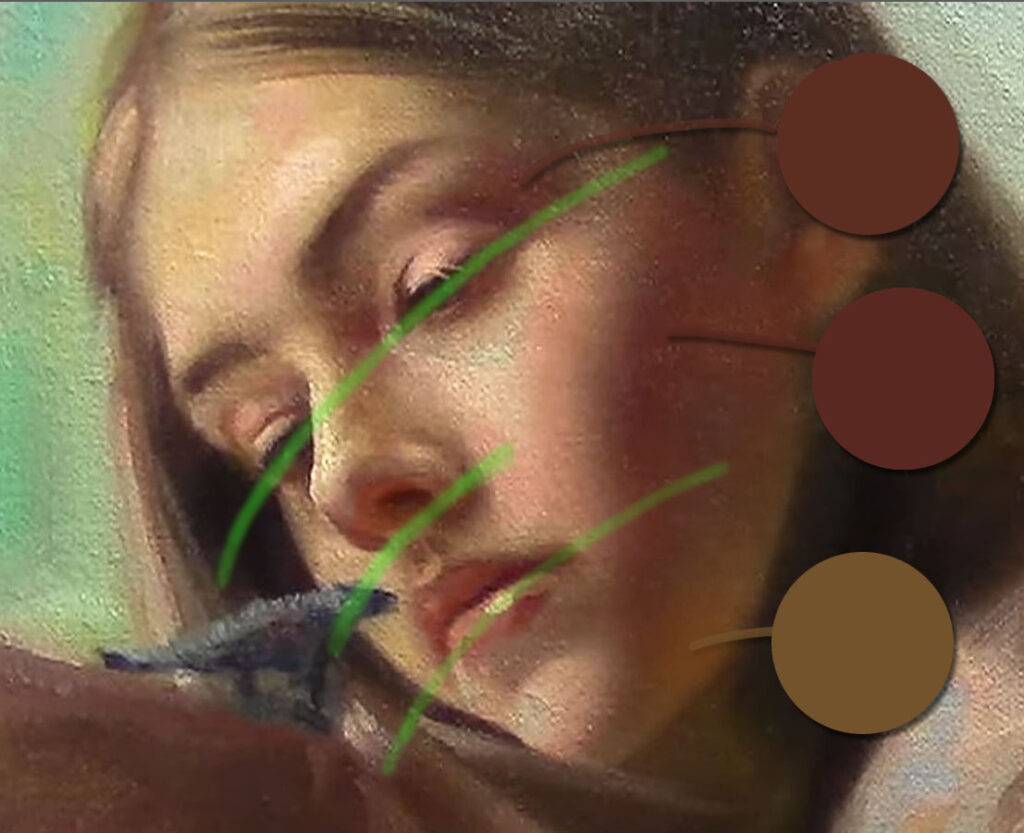

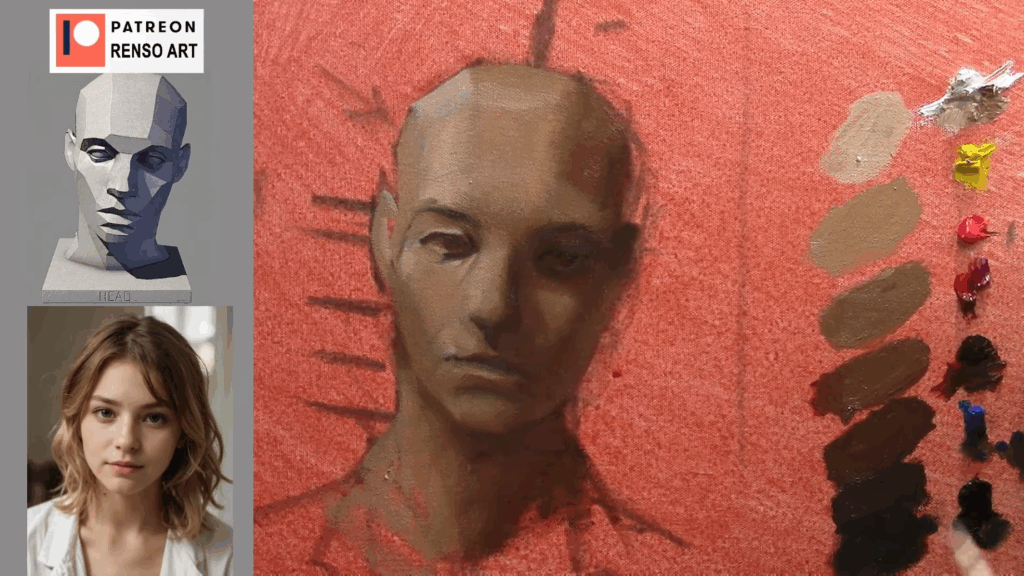

These turn away from the light and fall into shadow. Shadows on skin often contain cooler, desaturated versions of the skin tone—think mauves, blues, and soft grays. - Midtones (Transitional Planes)

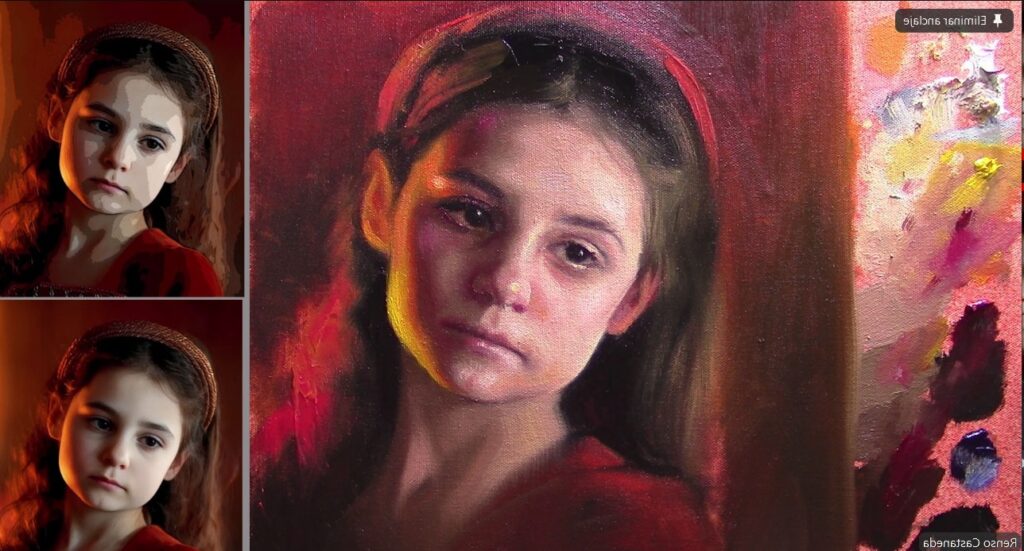

Between light and shadow, you’ll find subtle shifts: warm ochres, muted oranges, and browns. This is where artists often lose structure—learning to preserve these transitions is key to painting believable portraits. - Planes with More Blood Flow (Nose, Cheeks, Ears)

These areas are usually warmer and redder. Blood vessels closer to the surface add a rosy tone, especially in fairer skin. - Planes Affected by Bone or Cartilage (Brow Ridge, Jawline, Nose Bridge)

These may appear slightly cooler or have a greenish or bluish undertone, especially in thinner skin types or under cooler lighting.

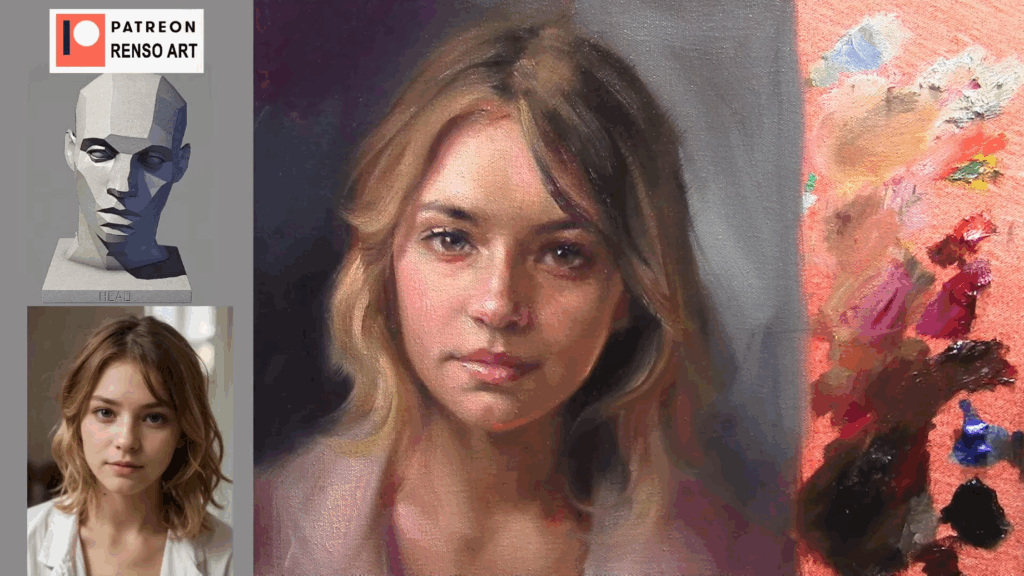

🌈 The “Zonal Color Theory” in Portraiture

Many traditional painters—like John Singer Sargent and Anders Zorn—understood that different zones of the face carry different dominant color temperatures:

- Forehead → Yellowish (due to bone and thin skin)

- Cheeks and Nose → Reddish (due to blood flow)

- Chin and Jaw → Cooler or more bluish (due to shadow and beard area in men)

This approach, sometimes referred to as “zonal color theory,” helps create vibrant yet believable skin tones.

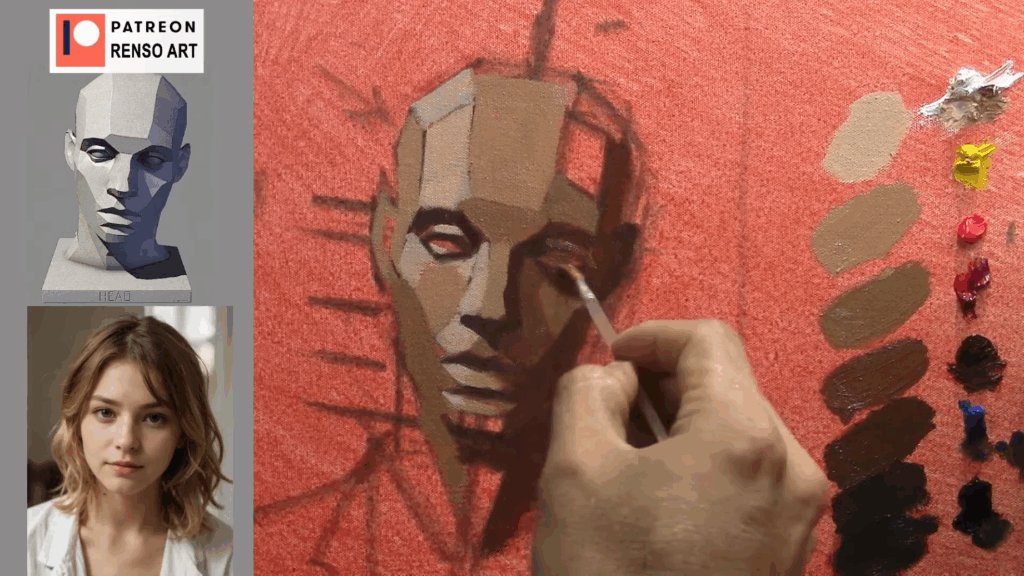

🖌️ Painting Tip: Don’t Blend Too Much

A common beginner mistake is over-blending the face, which erases the subtle changes between planes and flattens the form. Try blocking in colors with distinct edges first, then softly transition only where needed. The structure of the face is often lost in the blending—not the drawing.

👁️ Train Your Eye

Learning to see the planes of the face takes time. Try studying portrait sculptures or doing monochromatic studies (in one color) to focus only on value and form before reintroducing color. Over time, you’ll notice how light shapes the face through color, not just value.

Image suggestion: A simplified 3D model of the head with labeled planes and color zones.

Final Thoughts

Understanding and applying the color planes of the face will transform your portraits from flat to full of life. Light, form, and color all work together to create the illusion of depth. As you practice, you’ll begin to see the face not just as a collection of features, but as a landscape of subtle color and form.