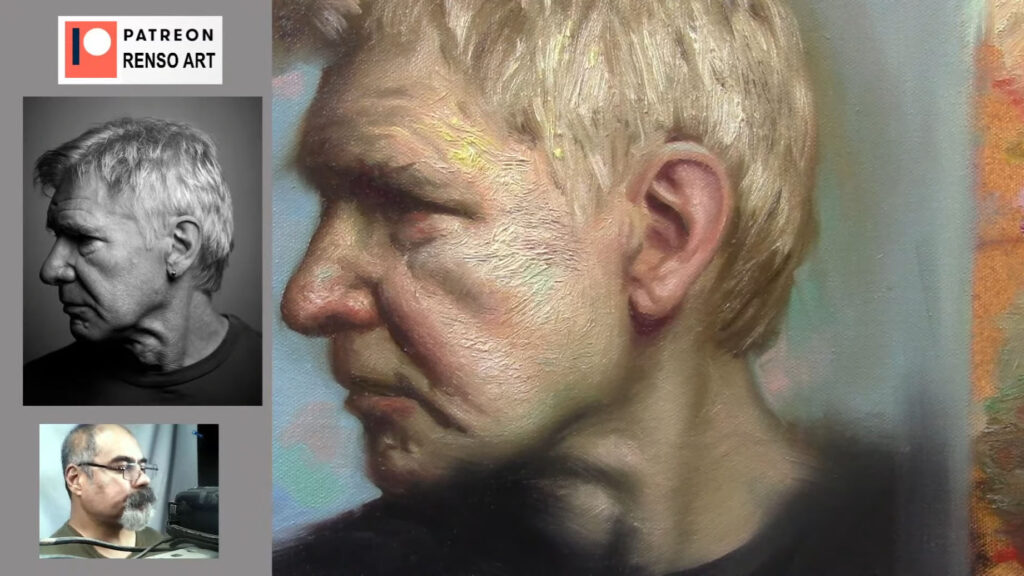

Struggling with your portraits? You might find my E-book helpful. Click here

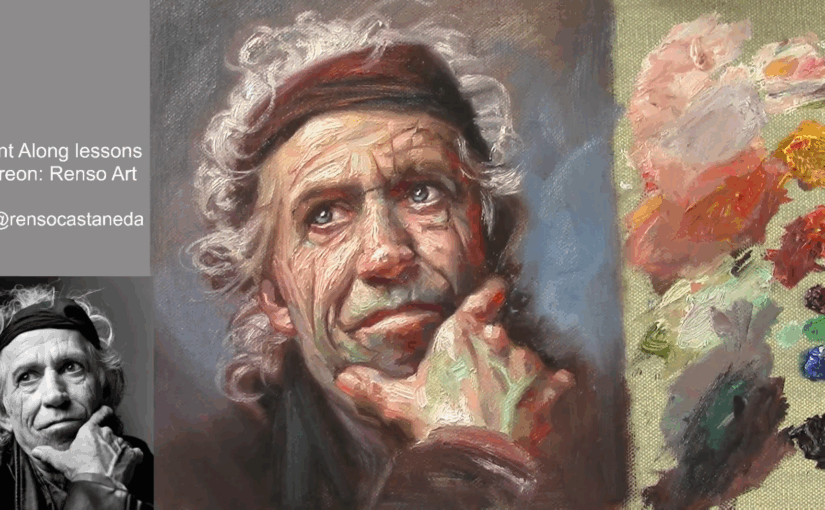

It took me a lot of time to understand that I did not needto paint details, I always expend a lot of time painting the eyes aoutlinining the eyelids, the result a cartonish portrait, but that did not stop to try again and again, and the result was worseI heard my teaches saying so many times, less is more but I did not get it it did not make sense for me, how less details would be more on a portrait.

I learnd more from my friends from the ones that listening the teachers and apply this rule less is more, I rem,ember specially ne of my friends, how his portraits looks so natural from a distance, so real and when I got closer to analize details, there was not details, from that day I understood that should see a painting a s a awhole a unity, not agroup of detailed eyes , nose and mouth is was another story try to get that degree of simplifications and softness, I ceated a bad habit trying to copy every single thing now I had to change this habit and everything started with big shapes, ignoring small parts, ignoring otulining the the eyes and more.

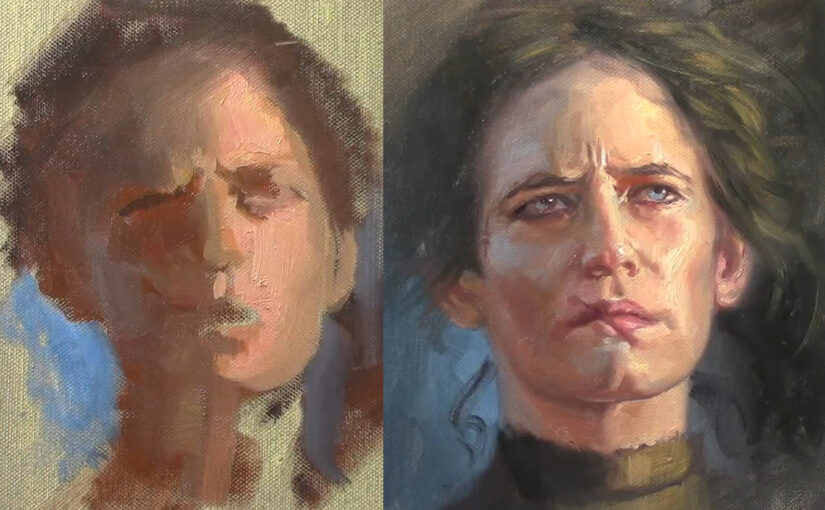

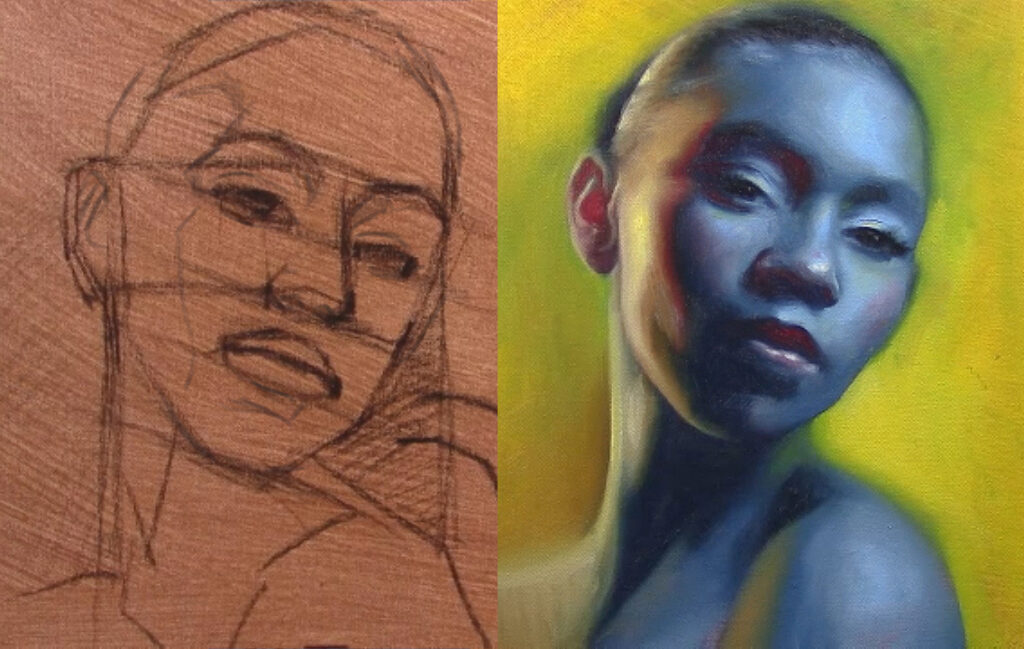

When painting a face, it’s tempting to chase the details too early—eyes, lips, little highlights. But the secret to a strong, lifelike portrait lies in how you begin. Starting with flat shapes and blocking in major values creates clarity, structure, and momentum. Only later do we move into form, blending, and more refined color. This step-by-step approach doesn’t just make portraits easier—it makes them better.

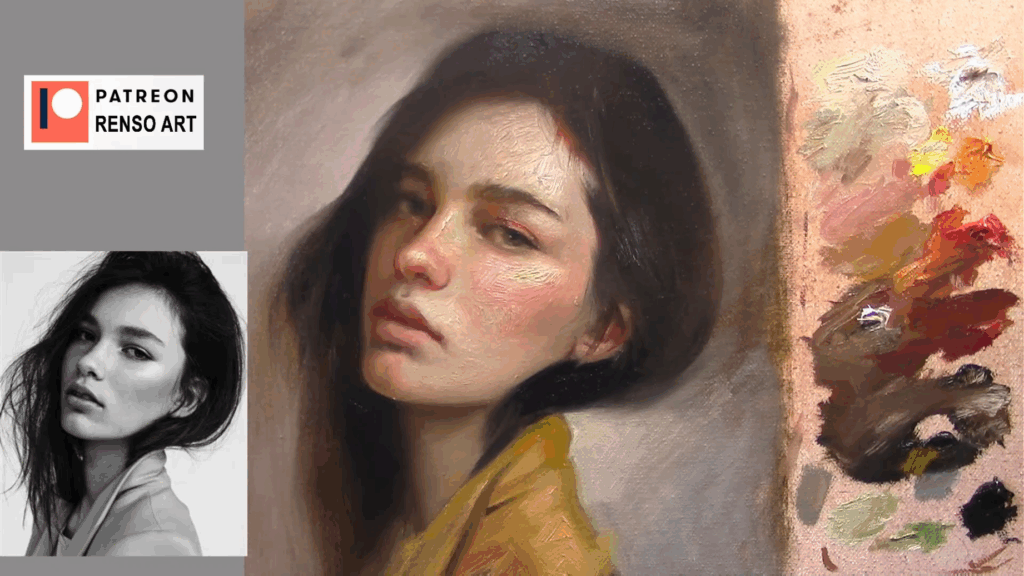

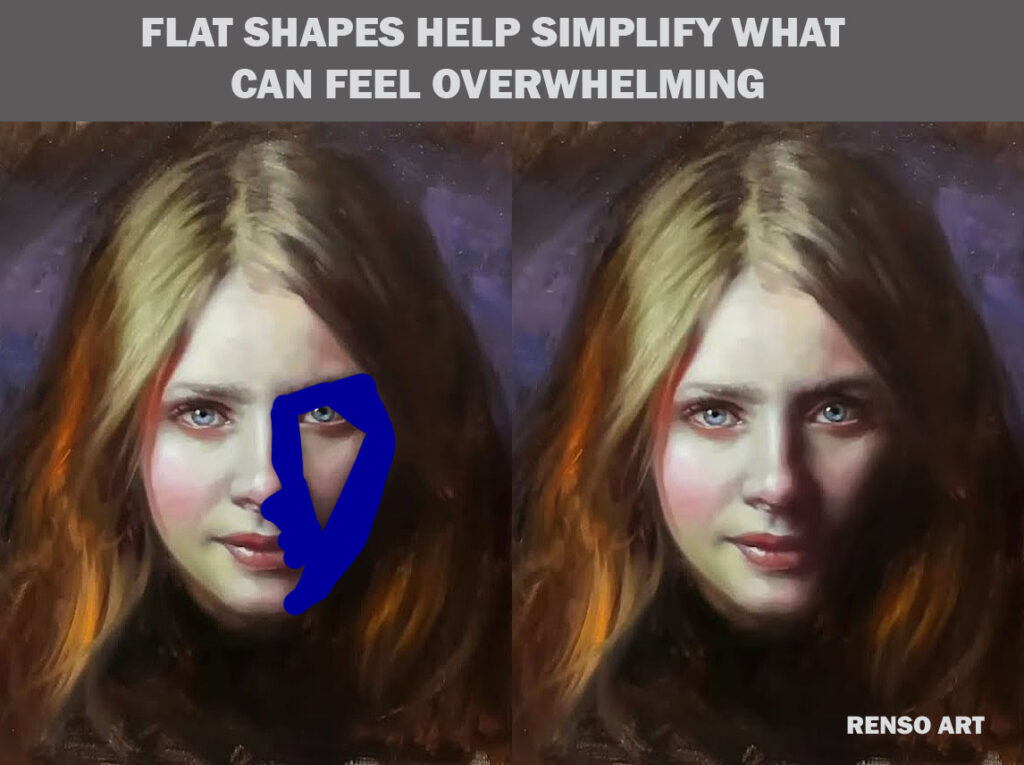

1. Why Flat Shapes First?

Blocking in the face with flat shapes is like setting the stage before the actors arrive. You’re laying down the big ideas: where the light falls, where the shadows sit, and how the head is turned in space.

Flat shapes help simplify what can feel overwhelming. Instead of trying to paint a “nose,” you paint a dark triangle. Instead of painting an “eye socket,” you drop in a midtone mass. These shapes establish a visual map. They remove the emotional pressure to get things “just right” too soon—and allow you to see your painting as a whole.

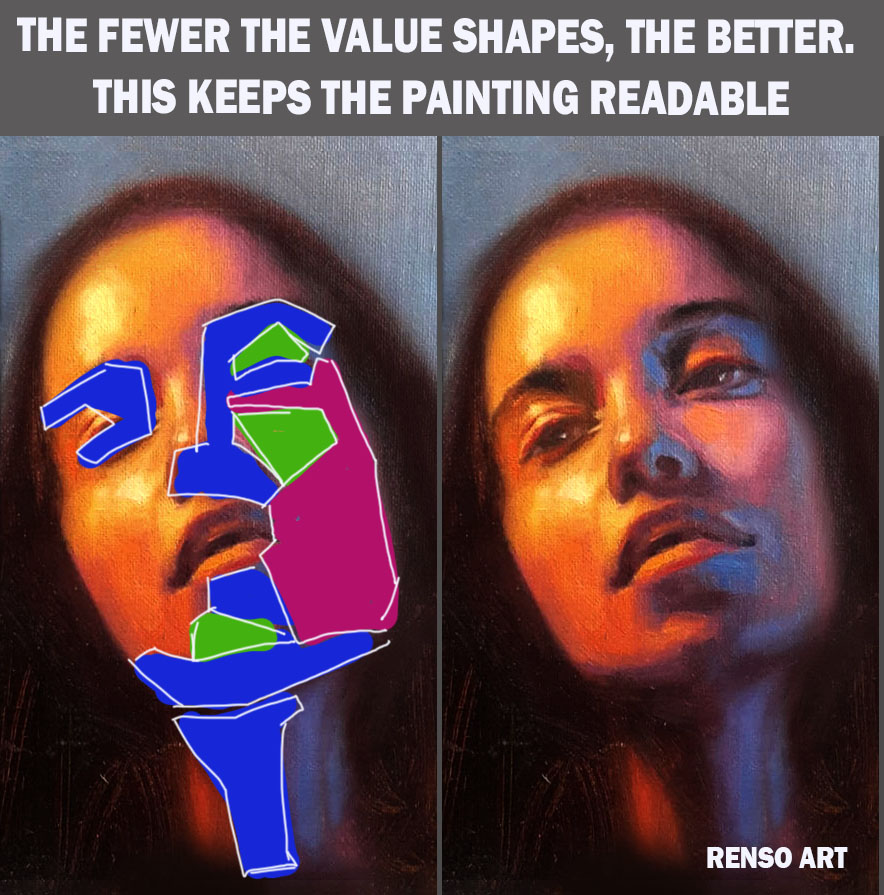

2. Keeping Values Clean and Simple

At this stage, you’re not blending. You’re being bold and decisive. Think of it like cutting pieces of colored paper to build a collage. The forehead might be one tone. The cheek, a slightly darker one. The shadow under the nose? A solid, deep value. The fewer the value shapes, the better. This keeps the painting readable, even from across the room.

This is also the best time to adjust proportions. It’s much easier to shift a big shape than to fix a fully rendered eye that’s half an inch too low.

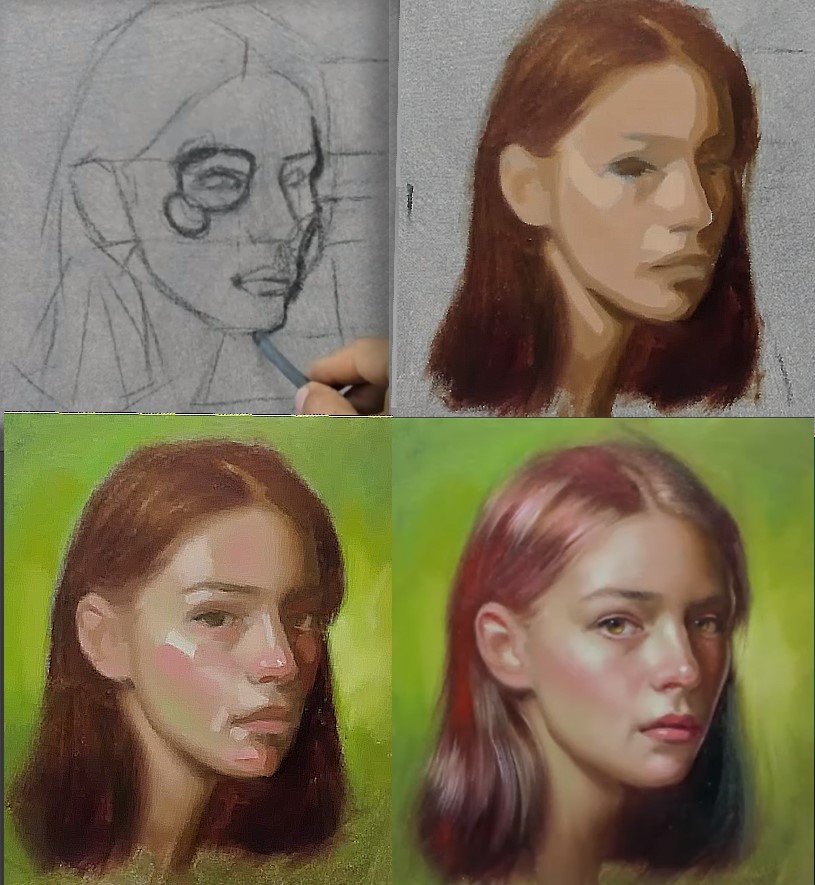

3. Transitioning Into Form

Once your flat shapes are in place and you feel confident in the structure, you can begin to blend. Now is when you shift gears—from graphic design to sculpture. You smooth the transitions between values to suggest roundness. You start seeing the cheekbone turn, the forehead curve, the nose project, for this part you need anatomy knowledge and know how to render primary forms (sphere)

This is where form begins to emerge. Suddenly, that flat color patch becomes a face with dimension.

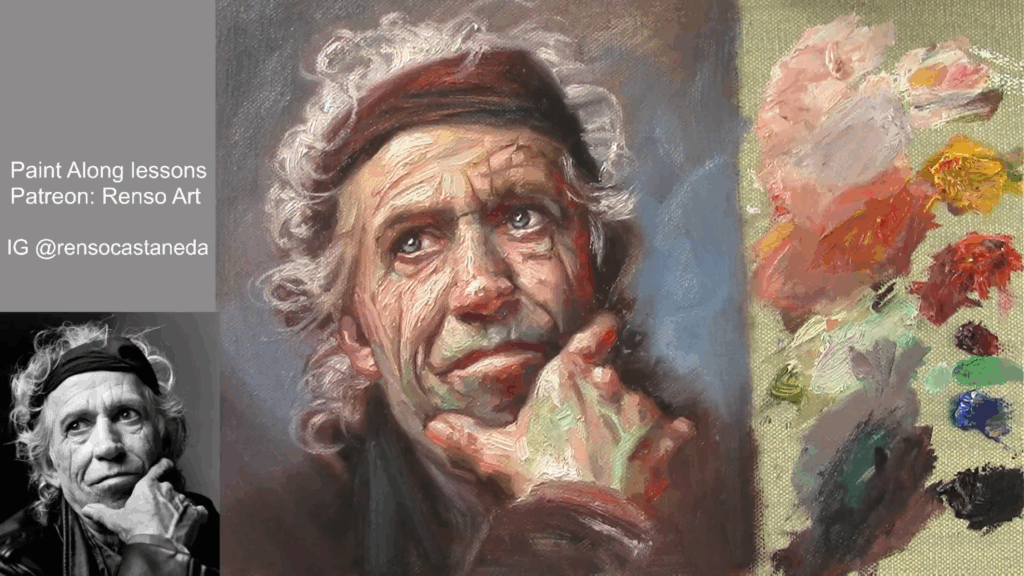

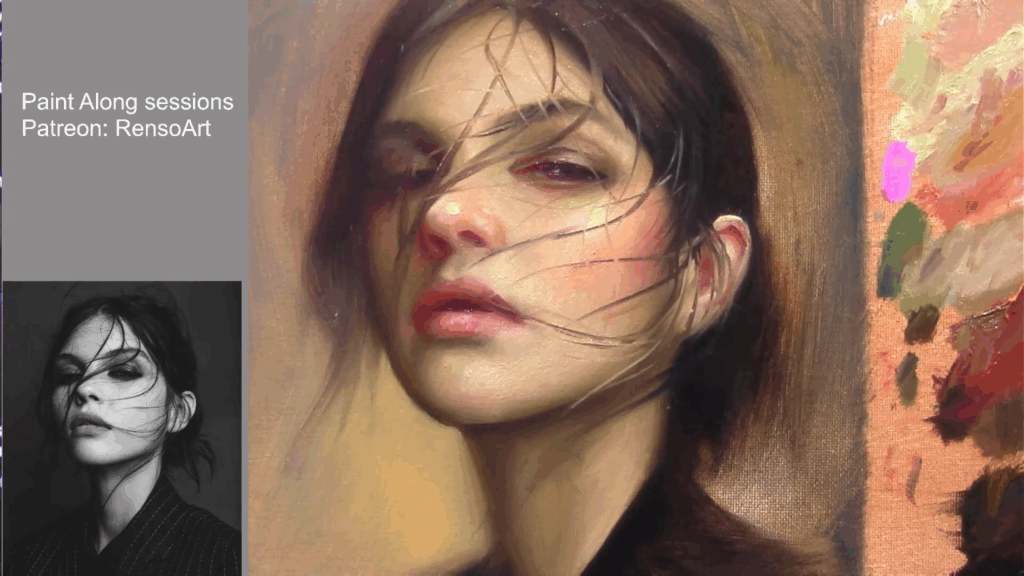

4. Introducing Subtle Color Variations

As you move into the blending and modeling phase, you can also introduce more color. Early on, you may have blocked in a simplified, warm tone for the light areas and a cooler tone for the shadows. Now, you can start letting small shifts in hue breathe life into the skin. Maybe the cheeks lean pink. The forehead picks up a golden note. The jaw cools into greenish tones.

Don’t think of these as decoration—they’re part of how form is communicated. The way skin catches light depends on temperature, not just value.

5. Patience, Rhythm, and Control

By separating the painting into phases—flat shapes first, blending second—you give yourself control. You also give your eye time to understand the face. You’re not rushing. You’re building.

This method gives your painting a rhythm. Each phase has a purpose. Each decision builds on the last.

Final Thoughts

Painting a face isn’t about chasing realism immediately. It’s about building structure first, then letting it evolve. Blocking in with flat shapes gives you clarity. Blending into form gives you life. And adding subtle color brings soul.

Whether you’re working in oil, acrylic, or digital media, this process—flat to form—is a timeless way to paint portraits with confidence and character.