Struggling with your portraits? You might find my E-book helpful. Click here

Every artist has a way of seeing. And how we see directly shapes how we paint. Some artists begin with careful outlines, building a painting like a drawing brought to life. Others start with masses and values, shaping the face as if carving it out of clay. These are the linear and sculptural approaches to painting—and understanding the difference can dramatically shift your process and results.

Let’s look at what defines each method, their strengths, and how they can work together.

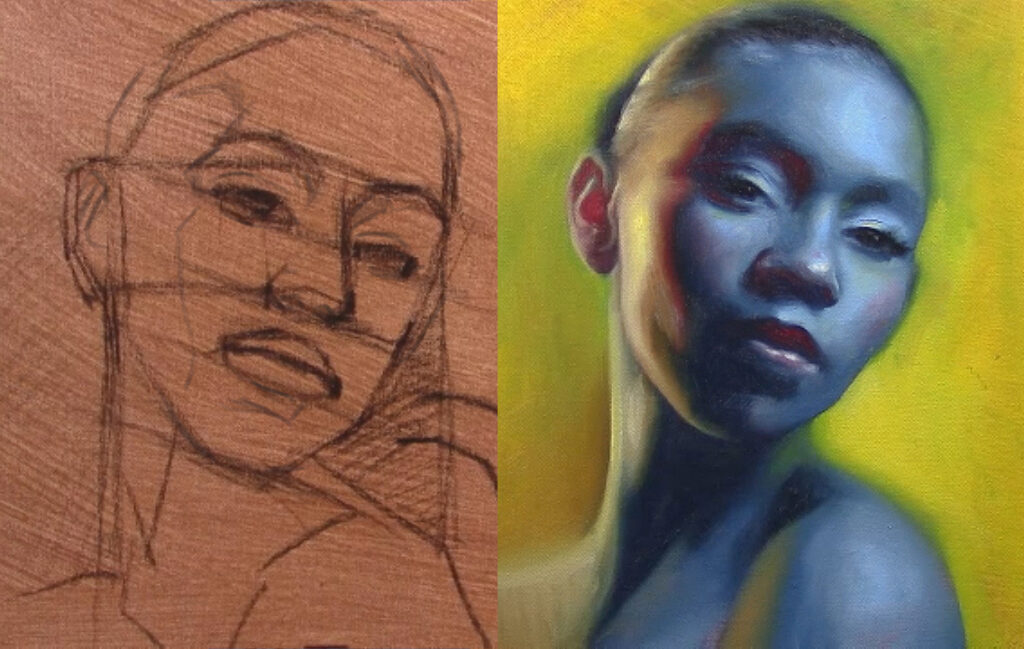

1. The Linear Approach: Drawing First

The linear approach starts with drawing—clear contours, careful placement, and strong edges. It’s about line and design. Think of Renaissance drawings or academic figure studies where every edge is defined before the painting begins.

In a linear process:

- The artist often begins with a detailed sketch.

- Emphasis is placed on accurate proportions and clean outlines.

- Painting becomes a process of “coloring in” the drawing, often staying within pre-drawn borders.

- Form is revealed through controlled shading and modeling.

This approach is especially useful when precision is critical—such as in commissions or likeness-driven portraits. It offers clarity and structure, making it easier to correct mistakes early on.

Strengths of the linear method:

- Strong control over proportions and likeness.

- Excellent for beginners who need to train their eye.

- Useful in tightly rendered, classical realism.

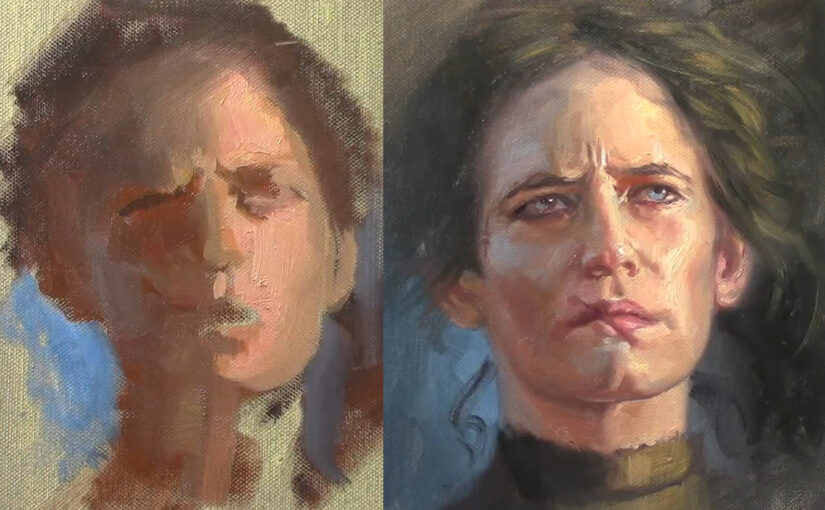

2. The Sculptural Approach: Mass First

The sculptural approach thinks less about edges and more about volume. It’s as if the artist is molding the face out of paint, starting with broad tonal shapes rather than detailed lines.

In a sculptural process:

- You block in big value masses right away—light vs. dark.

- Drawing happens within the painting, guided by the flow of light.

- Edges may remain soft and organic early on.

- The form emerges through modeling, not outline.

This is the approach you often see in painters like Sargent or Zorn—where the illusion of form and life seems to rise out of loose, confident brushwork.

Strengths of the sculptural method:

- Promotes seeing the subject as a three-dimensional form.

- Encourages expressive brushwork and painterly surfaces.

- Great for quick studies and alla prima (wet-into-wet) painting.

3. When to Use Each Approach

You don’t have to choose just one method forever. In fact, many artists blend the two.

- Use linear thinking when you want control—early in the piece, or when proportions really matter.

- Use sculptural thinking when you want life and movement—especially in light, shadow, and edges.

For example, you might begin with a loose, sculptural block-in, then overlay linear drawing to tighten the eyes and features. Or start with a clean linear sketch, then break out of it with juicy sculptural strokes in the cheeks and hair.

4. Which One Is Right for You?

If you’re a more analytical thinker, you may gravitate toward the linear approach. If you’re more intuitive or tactile, the sculptural method may feel more natural.

But the truth is: mastering both gives you freedom. It’s like being bilingual in the language of painting. You can switch modes depending on the subject, mood, or even your energy that day.

Final Thoughts

Painting is never one-size-fits-all. Whether you build your portrait like a cathedral (linear) or carve it like marble (sculptural), both methods are valid and powerful.

Try both. Explore. Observe which feels more natural—and which challenges you in good ways. Often, your best work comes from the dance between line and mass, between structure and gesture.

In the end, it’s not about choosing sides. It’s about expanding your tools so that your painting becomes not just a picture, but a conversation between what you see and how you feel.

This explanation of the two different processes is incredibly powerful to me, and exactly what I needed to hear today. I truly appreciate how you don’t advocate for one approach or outcome as being superior to the other… and your encouragement to explore both simultaneously, or to use any one exclusively, as the the need arises is wisdom I rarely hear from art teachers. I appreciate your generosity in sharing your knowledge. Your blogs are becoming an important part of my education. With much gratitude 🙏🏻

Love the way you explain! Love your paintings, the contrasts and that joy of colors and light! Thank you for sharing all this with us!

This is worded perfectly….it describes exactly how I like to create a portrait. For me it is almost always with a blend of both approaches. Sometimes it depends on my mood, or even the personality I want to depict from the subject. It also can depend if it is with a live model or a photo….commission or for self expression only. Whether I paint “tight” or “loose” can depend on my medium being used too. I paint with pastel much looser than oil paintings. The surface can make my approach differ too. If I paint on a rough or wood surface I would be looser than a “smooth as glass” foundation I had carefully gessoed. Renso, you teach beautifully and have earned your “Master” title! Thank you for putting words to these approach processes.