Recently, a student on Patreon asked me: “Why do I always get muddy colors?”

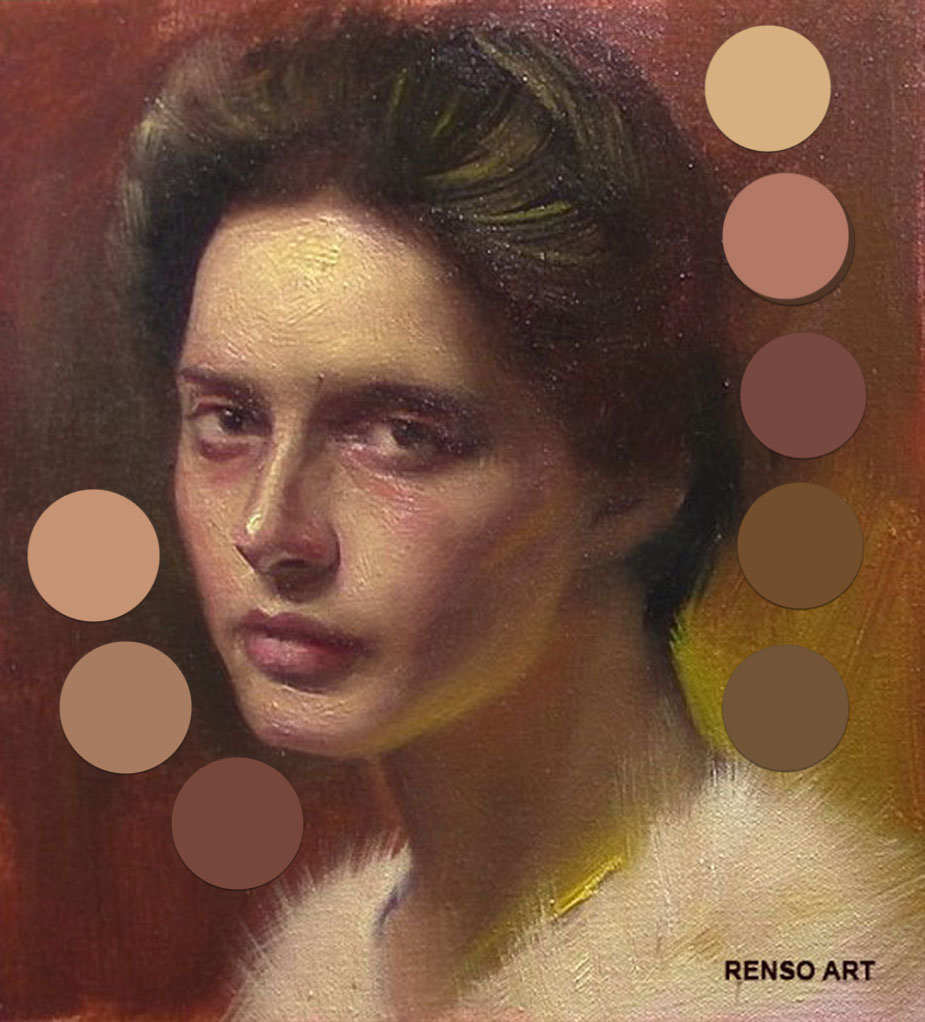

My answer was this: all the colors we use are muddy to some degree. The only “clean” colors are the pure ones straight from the palette—yellow, orange, red, green, blue etc. As soon as we start mixing, they begin to desaturate and shift toward gray. The more colors we add, the stronger this effect becomes.

And it doesn’t stop at the palette. Once we put paint on the canvas and start moving the brushstroke around to “find the right spot,” the paint keeps mixing. If we keep adding more strokes and then blend to smooth transitions, the mixture continues to dull little by little until it looks muddy.

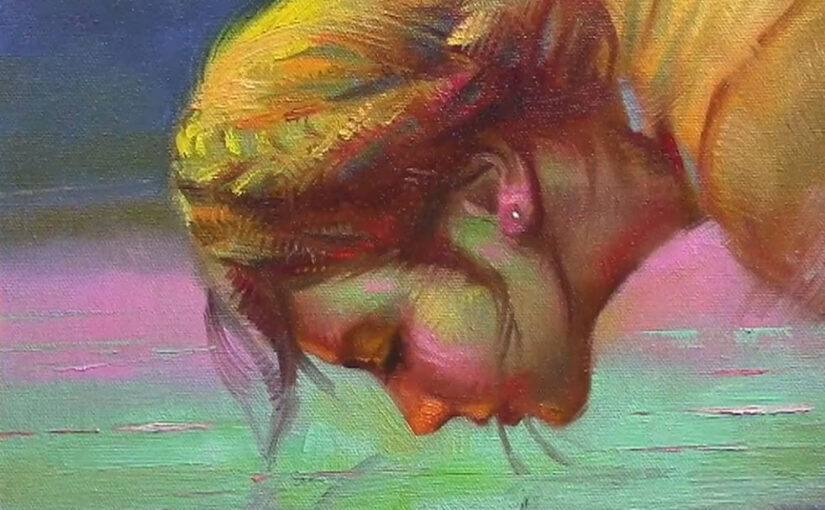

With experience, you start to anticipate what will happen with your colors. Sometimes, for example, I’ll drop in a touch of pure orange on the skin and blend just slightly—I end up with a fresh, clean tone because I balanced the mixture with a primary color. The trick is in the pressure of the brush and how much of that pure color you add. Too much, and it changes the mixture completely.

Another approach is to place your color down and resist the urge to move it too much. Beginners often expect colors to stay the same on the canvas as they looked on the palette, but in practice, brushwork and blending change everything.

Struggling with your portraits? You might find my E-book helpful. Click here

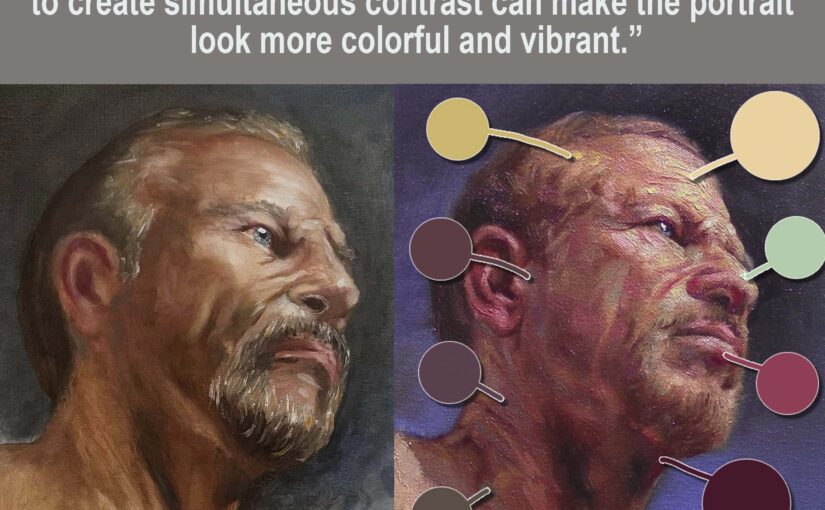

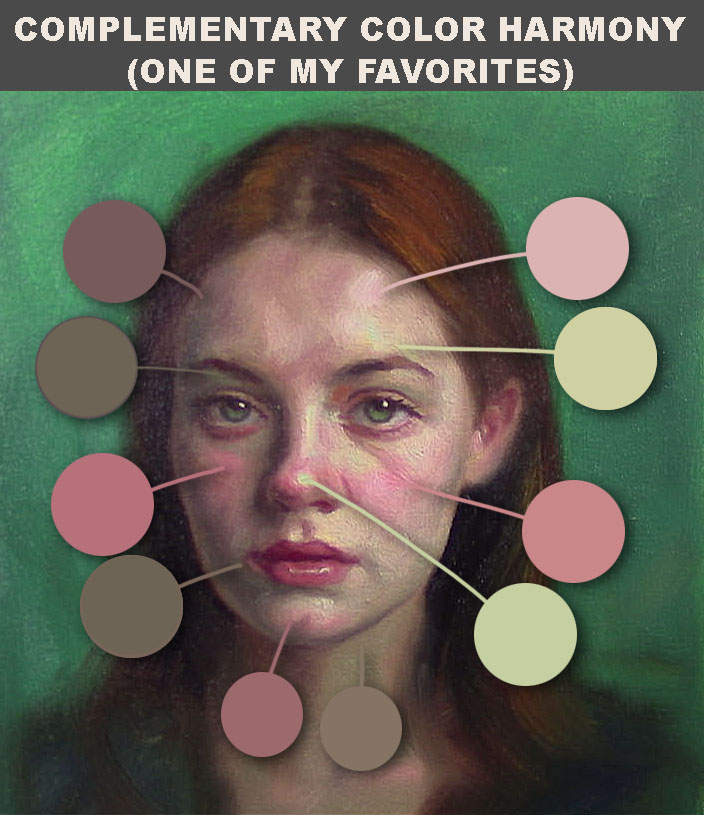

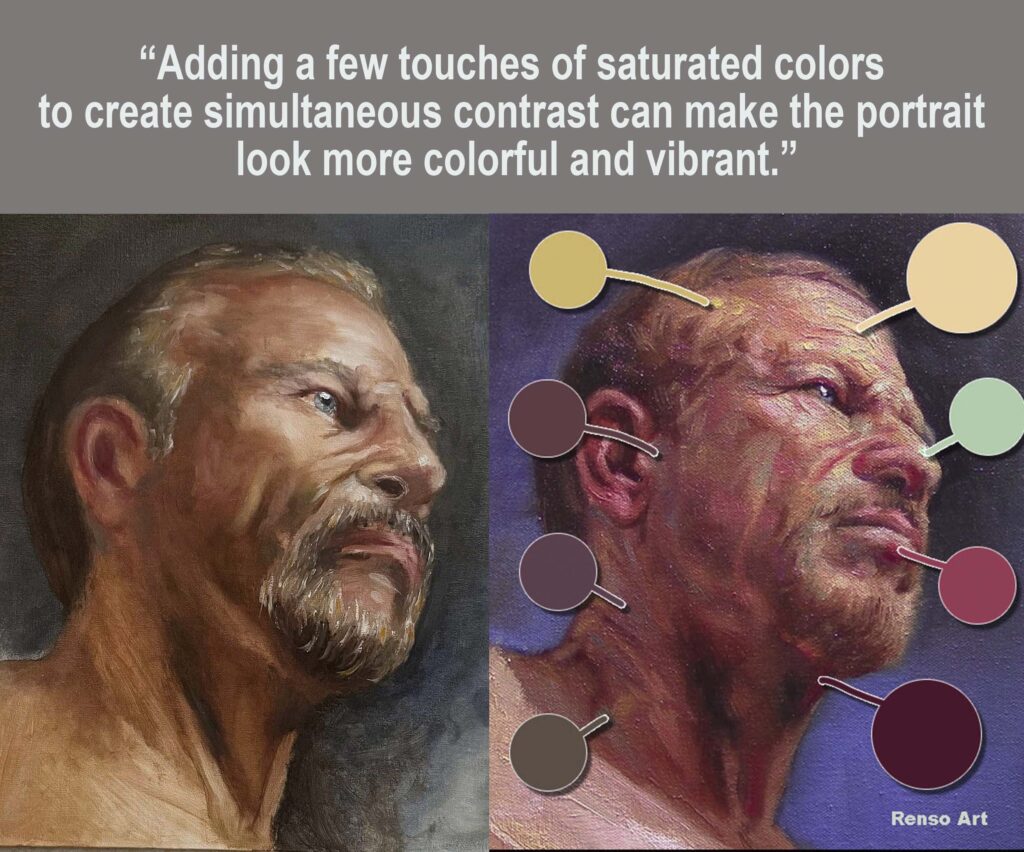

The best way to fix it without saturating the skin color too much : “Adding a few touches of saturated colors to create simultaneous contrast can make the portrait look more colorful and vibrant.”

Common Causes of Muddy Colors

1. Too Many Colors Mixed Together

When you keep adding more and more pigments, you’re really mixing all three primaries together (red, yellow, and blue). The result is a neutral, grayish-brown tone.

Tip: Limit your palette when mixing. Often two colors—and sometimes just a touch of a third—are all you need. Try to keep your mixtures clean and direct.

2. Using Opaque Paint in the Wrong Place

Some paints are naturally opaque, and when layered carelessly, they can kill the brightness of the color underneath.

Tip: For glazing or subtle layering, choose transparent colors. Save your opaque paints for highlights or solid passages.

3. Not Cleaning the Brush Enough

If your brush still has leftover paint from a previous stroke, it contaminates your mixture before you even realize it.

Tip: Wipe or wash your brush between different mixtures, especially when switching between warm and cool colors.

4. Confusing Warm and Cool Colors

Mixing a warm version of a color with its opposite temperature can quickly dull the mixture.

Tip: If you want bright mixes, combine warm with warm or cool with cool. Use temperature shifts carefully.

5. Painting Over Wet Layers Without a Plan

In oil painting especially, working wet-into-wet without control can easily muddy colors. Too much brushing makes everything blend into a flat tone.

Tip: Place your strokes and leave them alone. Think of it like cooking—too much stirring spoils the soup.

Final Thoughts

Muddy colors happen to everyone, even experienced painters. The key is awareness. Keep your palette simple, clean your brush often, and think about the temperature and transparency of the paints you’re using. With practice, you’ll start to predict how your colors will behave and learn when to let a brushstroke sit on its own.

When you get this balance right, your colors will look fresher, brighter, and more alive—and painting will feel a lot more rewarding.