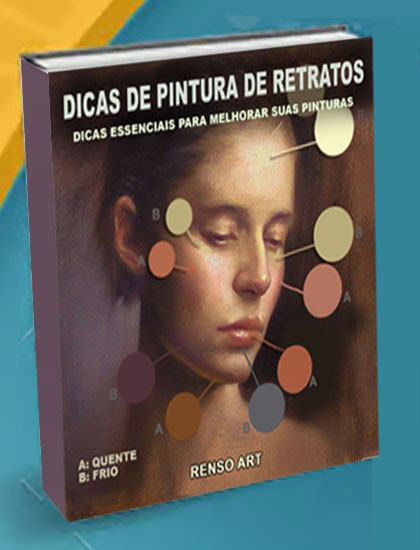

Struggling with your portraits? You might find my E-book helpful. Click here

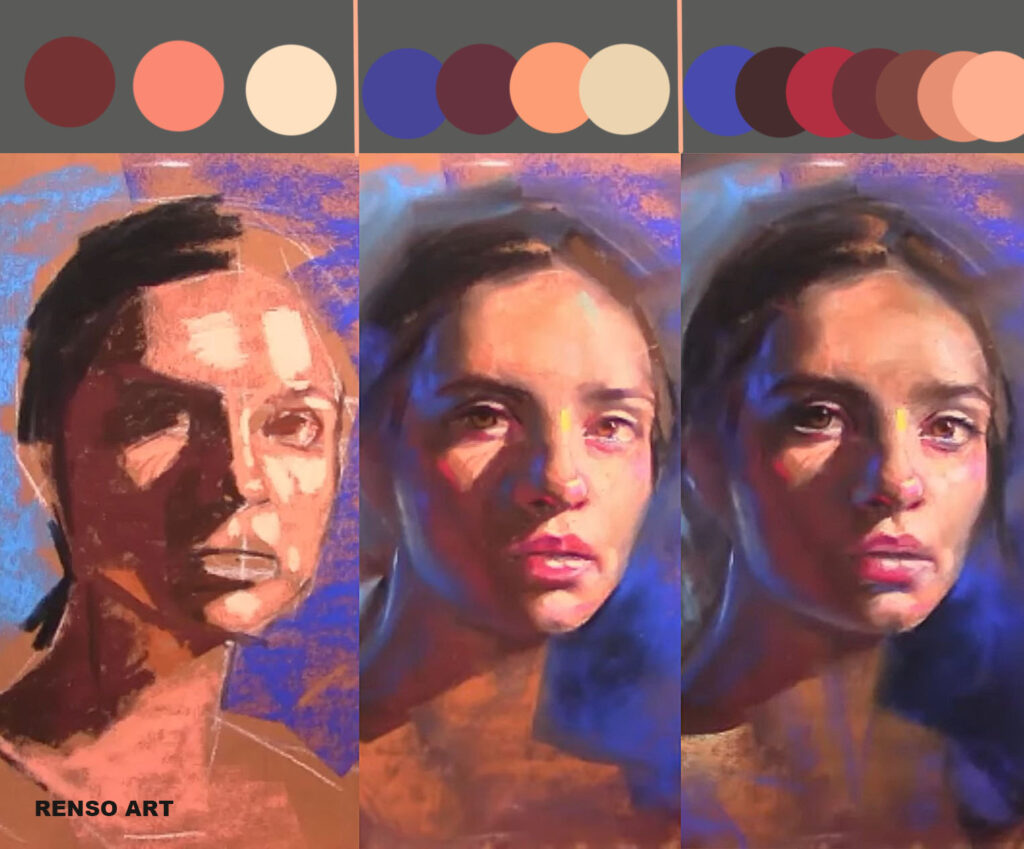

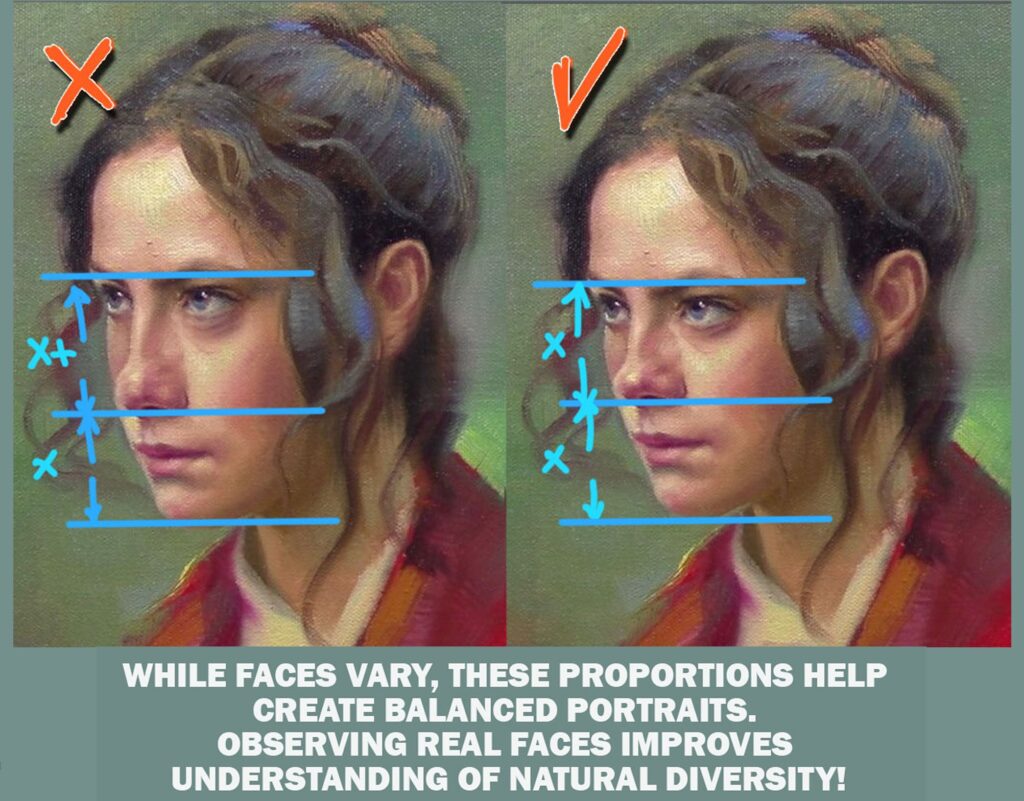

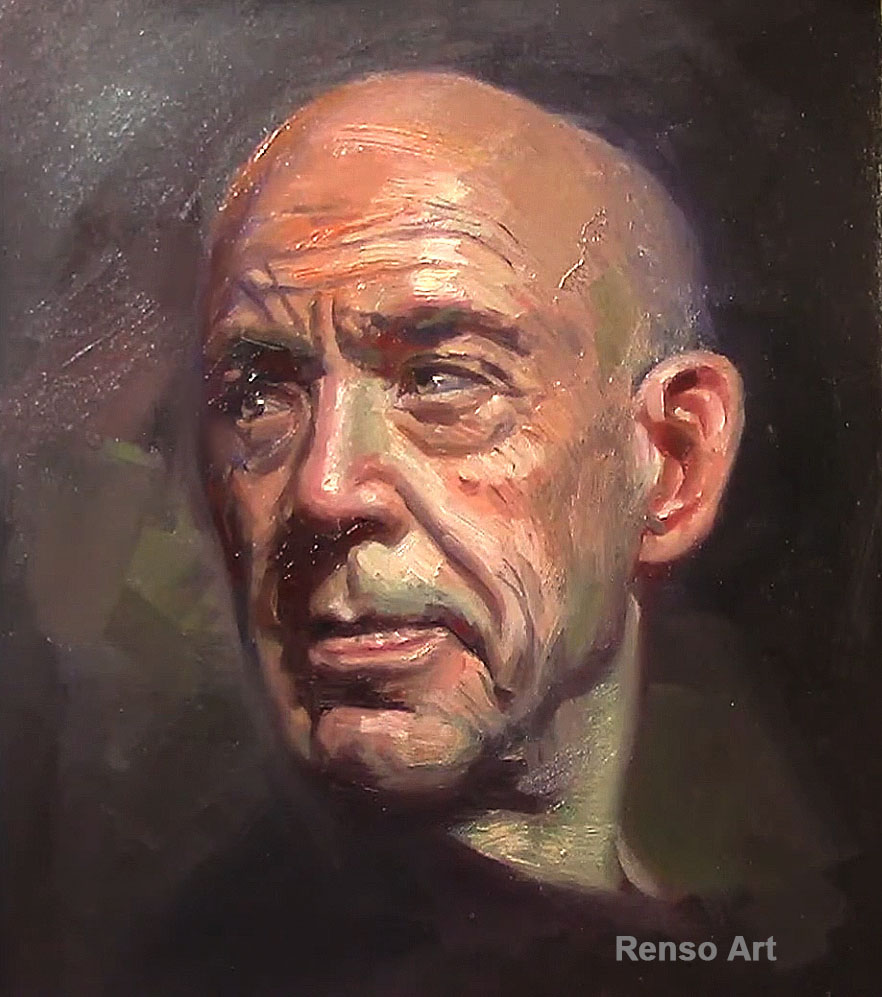

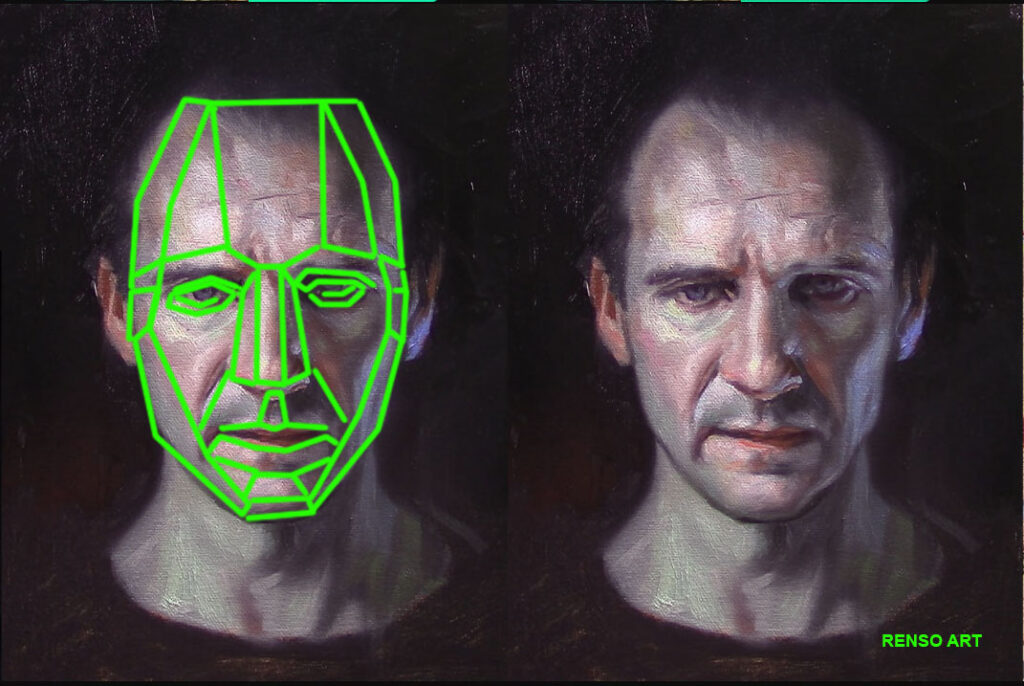

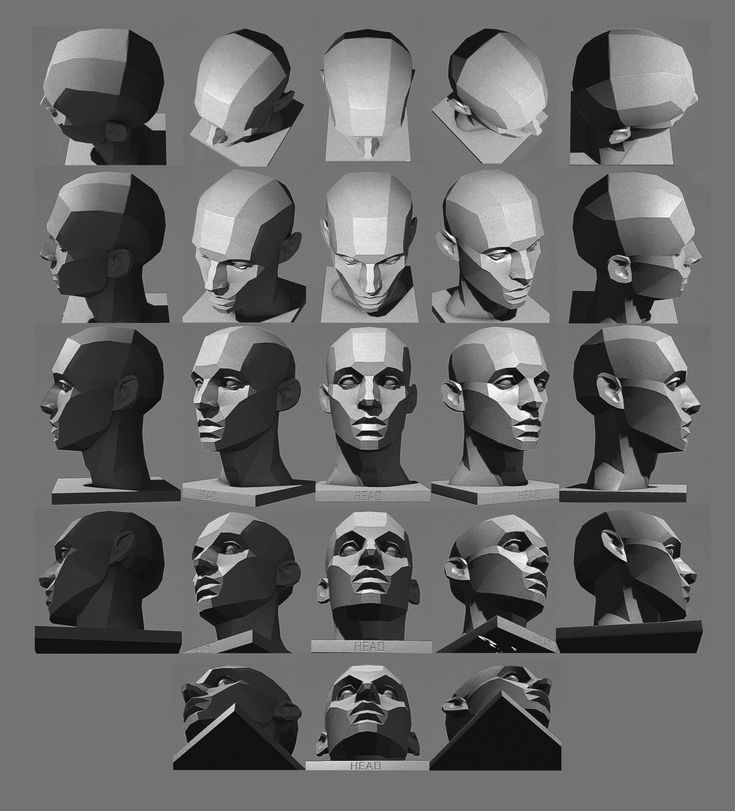

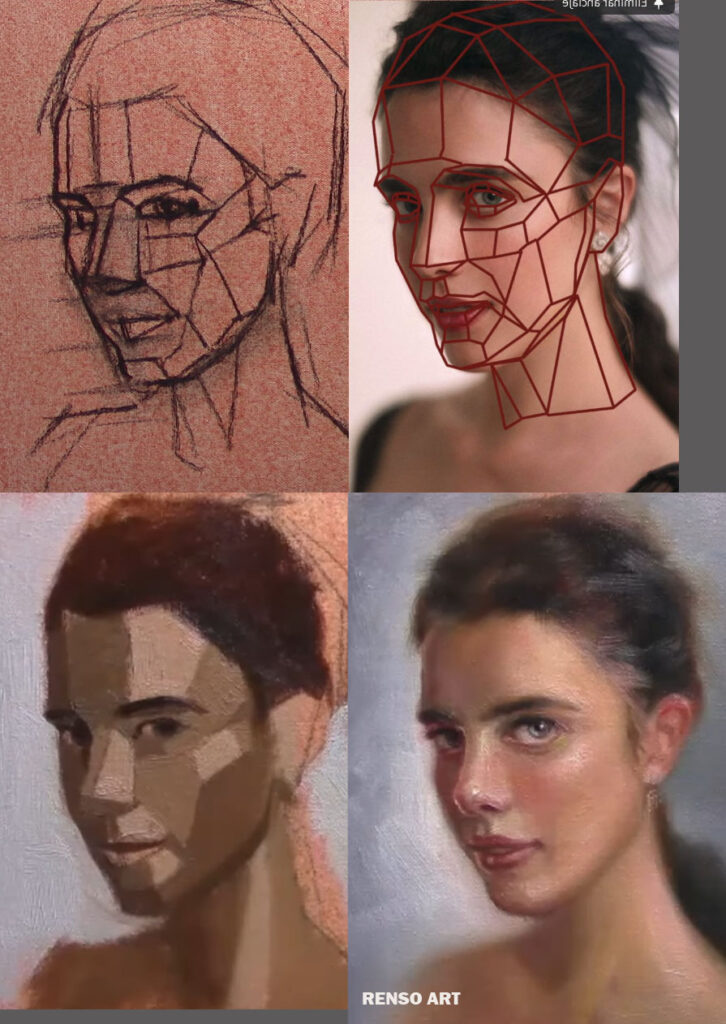

When we first learn to paint the planes of the face, everything can look a little too hard — like carved stone. It’s normal. At the beginning, we focus on defining the structure, finding those clear divisions between light and shadow. But as we grow, the challenge becomes learning how to keep that structure while making the transitions soft and natural. That’s where realism begins.

The goal isn’t to erase the planes, but to understand them so well that you can blend them without losing their direction. Every soft transition you paint still belongs to a specific plane — it has an angle and a purpose. When you keep that in mind, your portraits stay solid even when the edges melt beautifully into the light.

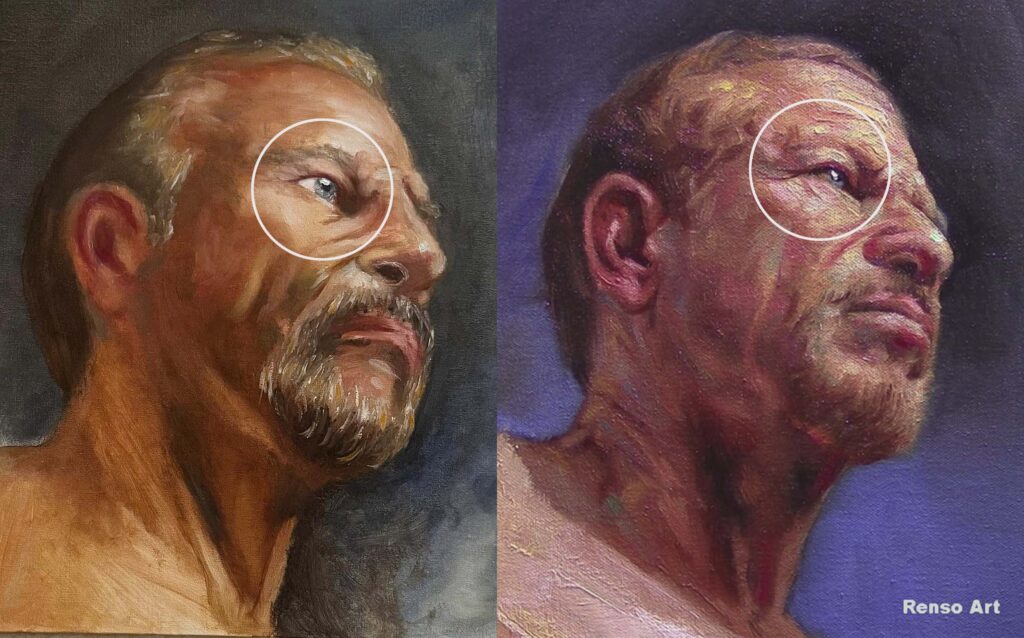

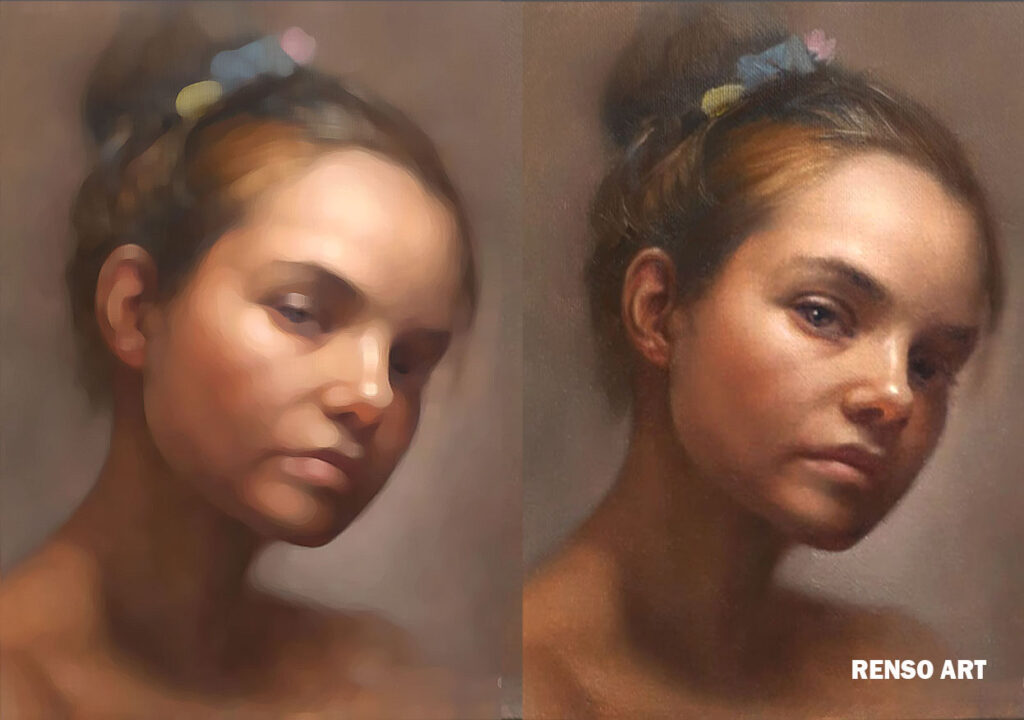

One thing that helped me was thinking of the face as a sculpture covered with thin fabric. The fabric wraps softly around the form, but the structure underneath never disappears. When you blend too much, it’s like covering the sculpture with a heavy blanket — all the shapes vanish. So instead of blurring everything, try to keep some edges alive. Let some planes meet sharply, and let others fade slowly. This balance gives your portraits both clarity and softness.

How to Soften the Planes Naturally

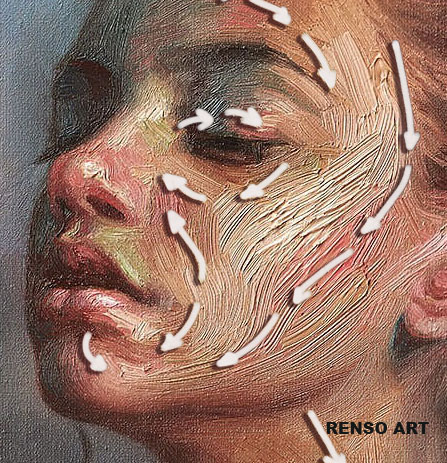

1. Blend with Purpose

When you blend, ask yourself what direction the plane is turning. Don’t just move the brush randomly — follow the form. A small circular motion might flatten the area, while a longer stroke in the right direction keeps the structure clear.

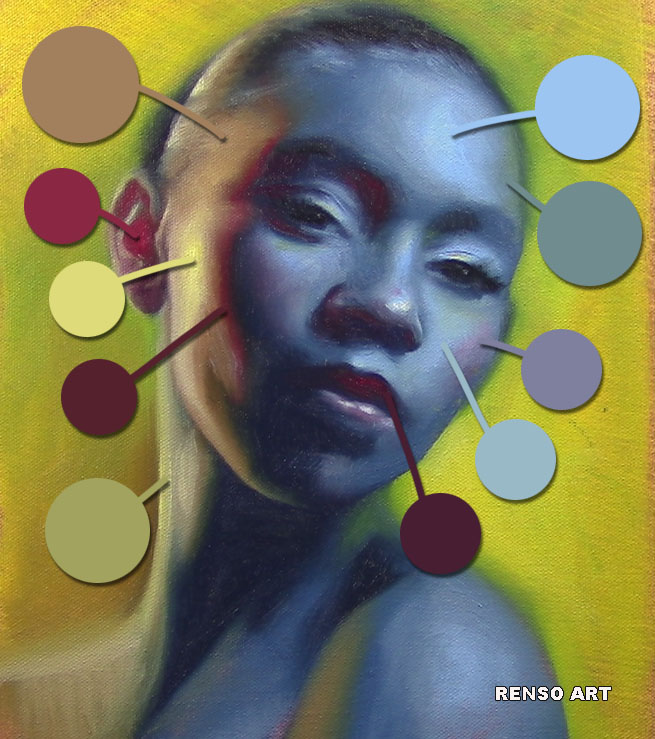

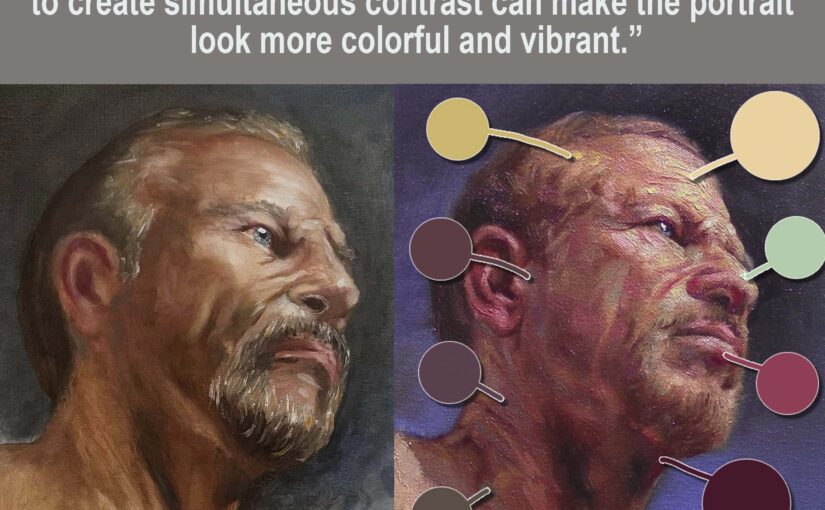

2. Keep Value Control

Soft edges don’t mean muddy values. If the value jump between planes is too small, everything will look flat. Keep your light and shadow families separate, and soften only the edges that belong between them.

3. Vary Your Edges

Real faces have sharp, medium, and soft edges. For example, the edge between the nose and cheek can stay sharp, while the transition on the forehead can stay soft. This variety gives the portrait rhythm and realism.

4. Observe the Light Source

Soft light creates gentle transitions; hard light keeps edges crisp. When painting from life or photos, adjust your edges to match the lighting. This keeps the painting truthful to the source.

Practice: Keeping the Planes Alive While Blending

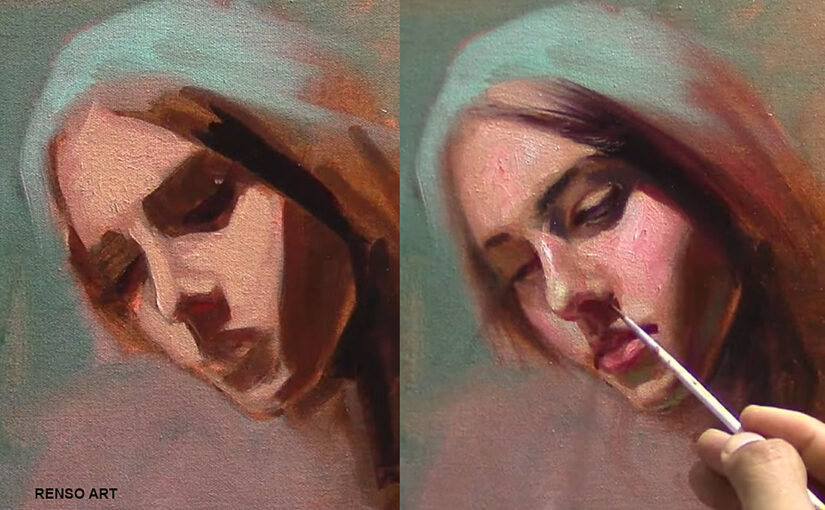

1. Block-In First, Blend Later

Start with strong, clear planes — don’t worry about softness yet. When your structure looks solid, then begin to blend carefully, keeping the direction of the planes. This helps you maintain form even as you refine.

2. Paint Half the Face Hard, Half Soft

This is a great exercise. Paint one side of the face with sharp edges and the other side softly blended. Then try to meet in the middle — balance both sides until the portrait feels realistic but still solid.

3. Use the Brush Like a Sculpting Tool

Think of each stroke as carving or wrapping around the head. Use the side of the brush for soft transitions and the tip for crisp accents. Small variations in pressure can make all the difference.

When you learn to soften without losing the structure, your portraits start to breathe. The planes are still there — guiding the light, shaping the expression — but now they feel alive under the paint. Realism is not about copying the surface; it’s about understanding the form and letting light reveal it gently.