Portrait painting is fun but also very challenging. Beginners usually run into the same problems, and that can slow down progress. The good thing is, once you know the issues, it’s much easier to fix them.

From my own experience, and from seeing what many new painters struggle with, here are the most common mistakes in portrait painting and some tips to avoid them.

Struggling with your portraits? You might find my E-book helpful. Click here

1. Weak Foundation Drawing / Underpainting

Issue: Starting with a vague or inaccurate sketch creates proportion mistakes that get worse as you build layers.

Fix:

✔ Begin with a simple block-in using clear shapes.

✔ Check proportions often (sight-size and Loomis proportions can help).

✔ Correct errors in the drawing before painting.

2. Poor Reference Photos

Issue: Low-contrast, blurry, or heavily filtered images distort features and colors, making accuracy impossible.

Fix:

✔ Work from sharp, well-lit photos (higher contrast works best).

✔ Avoid strong filters.

✔ From life? Make sure your subject is well lit.

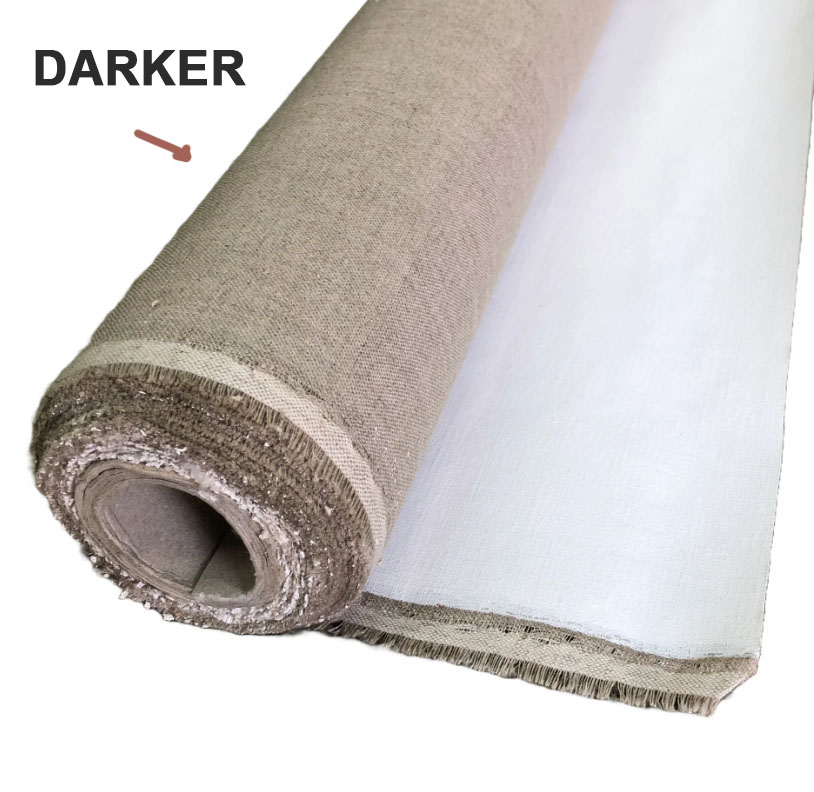

3. Skipping Canvas Preparation

Issue: Painting on cheap or unprimed surfaces causes paint to sink in, colors to dull, and blending to suffer.

Fix:

✔ Use a properly primed canvas or panel.

✔ Add an extra layer of gesso.

✔ Tone the surface with a neutral wash (like burnt umber) to reduce glare from white.

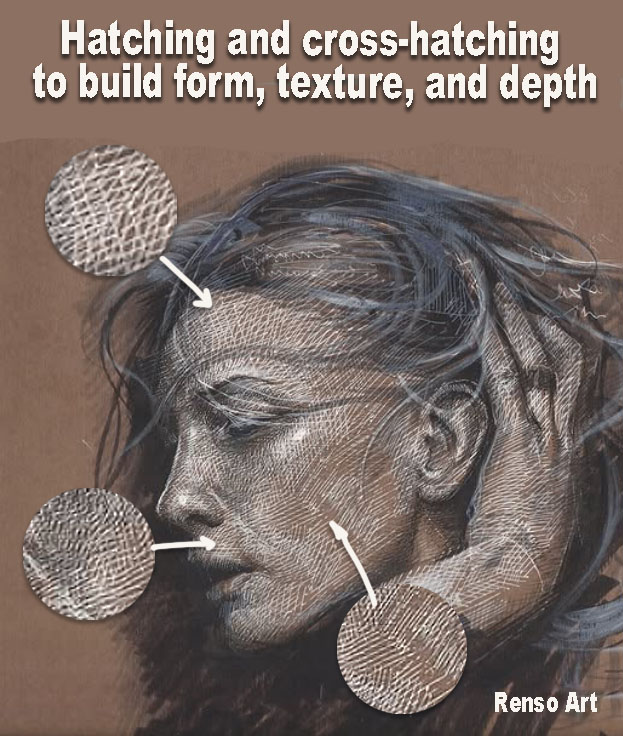

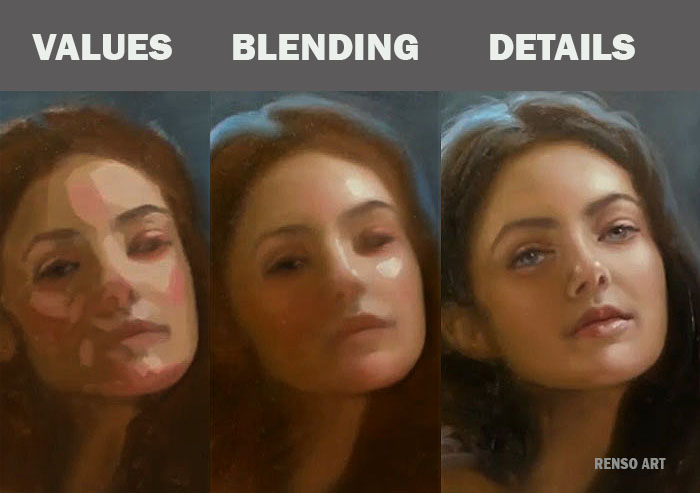

4. Over-Detailing Too Early

Issue: Jumping into eyelashes or highlights before establishing big shapes creates a patchy, disjointed portrait.

Fix:

✔ Squint to simplify values into large planes.

✔ Lay in main light and shadow areas before details.

✔ Think of the head as big structural planes, not lines.

5. Shadows Too Weak

Issue: Fear of darks makes shadows look flat or gray, leaving the portrait without depth.

Fix:

✔ Push shadows darker and richer than you expect.

✔ Transparent pigments (burnt umber, alizarin crimson) add depth.

✔ Beginners should avoid pure black—advanced painters can use any black but you can mix a chromatic black (ultramarine + alizarin or black + color).

6. Flesh Tones Too Pale

Issue: Overusing white results in chalky, lifeless skin.

Fix:

✔ Begin with middle values—earth tones mixed with reds/greens.

✔ Never use pure white in shadows.

✔ Observe real skin—it contains subtle shifts of reds, greens, and violets.

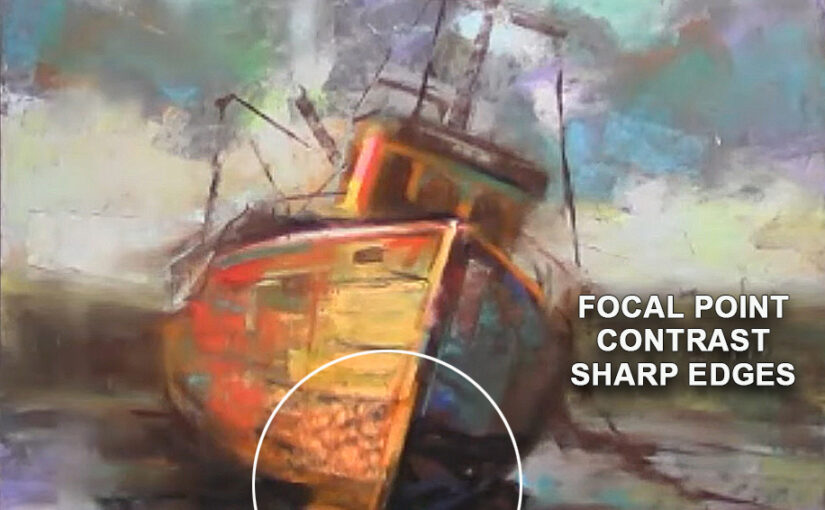

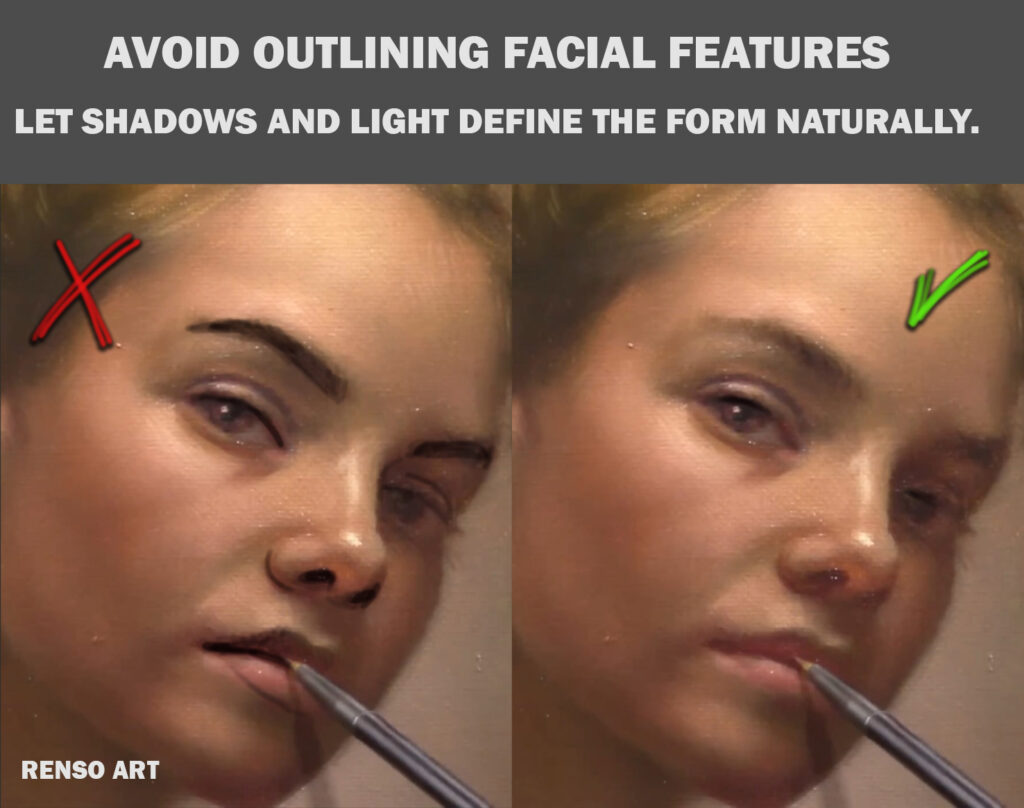

7. Too Many Harsh Edges

Issue: Crisp lines everywhere make features look cut out and artificial.

Fix:

✔ Blur edges where the form turns away from the light.

✔ Reserve sharp edges for accents in focal points (like the eyes or mouth corners).

✔ Use dry brushing or feathering for gentle transitions.

8. Disorganized Palette

Issue: A messy palette leads to muddy color mixtures and wrong values.

Fix:

✔ Arrange paints in a consistent order (warm/cool, light/dark).

✔ Wipe mixing areas regularly.

✔ Begin with a limited palette to learn values.

Final Thoughts

Every artist makes these mistakes at first—the key is recognizing and correcting them. By focusing on strong fundamentals (drawing, values, edges, and color mixing), your portraits will improve dramatically.

Which of these mistakes do you struggle with the most? Let me know—I’d love to help with more detailed tips!

(Bonus tip: Study master portraits—Rembrandt, Sargent, and Zorn are great for learning brushwork and color harmony!)