Struggling with your portraits? You might find my E-book helpful. Click here

A great painting is more than just a copy of reality—it’s a balance between observation, knowledge, and artistic intention. Should you paint exactly what’s in front of you? Should you rely on what you know about form and structure? Or should you push beyond reality to create something more expressive? The truth is, the strongest artwork often combines all three approaches.

1. Painting What You See (Observation)

The Foundation of Realism

Painting what you see means training your eye to observe shapes, colors, and values without letting preconceptions distort them.

Why It’s Important:

- Helps you capture accurate proportions, lighting, and color relationships.

- Prevents symbol drawing (e.g., painting an eye as a generic almond shape instead of the unique form in front of you).

- Develops your ability to notice subtle shifts in edges and tones.

Challenges:

- Our brains trick us—we tend to simplify or exaggerate what we see.

- Lighting conditions change, altering colors and shadows.

- Photographs lie—they distort perspective and flatten depth.

How to Improve:

✔ Draw/paint from life as much as possible.

✔ Squint to simplify values and ignore unnecessary details.

✔ Compare relationships (e.g., “Is this shadow warmer or cooler than that one?”).

2. Painting What You Know (Knowledge)

The Structure Beneath the Surface

Even when painting from observation, you must rely on anatomy, perspective, and color theory to make your work convincing.

Why It’s Important:

- Helps you correct mistakes when your eyes deceive you.

- Allows you to paint from imagination when references are lacking.

- Gives your work solidity and believability, even in loose styles.

Key Areas of Knowledge:

- Anatomy (bones, muscles, how light wraps around form).

- Light & Shadow (core shadows, reflected light, temperature shifts).

- Perspective (foreshortening, spatial relationships).

- Color Harmony (how colors interact under different lighting).

How to Apply It:

✔ Study fundamentals even when working from reference.

✔ Fix errors logically—if a shadow looks “off,” check if it aligns with light direction.

✔ Practice constructive drawing (building forms from basic shapes).

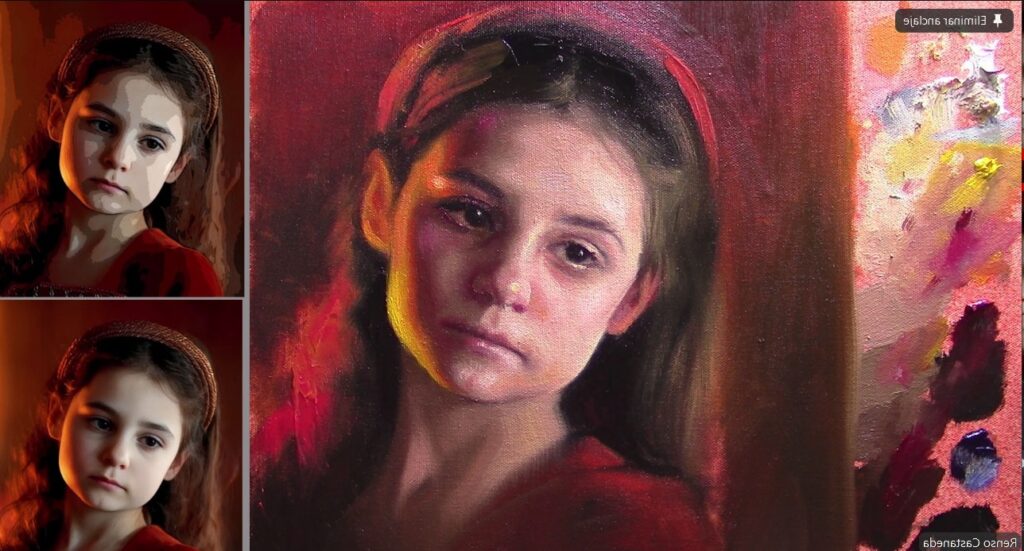

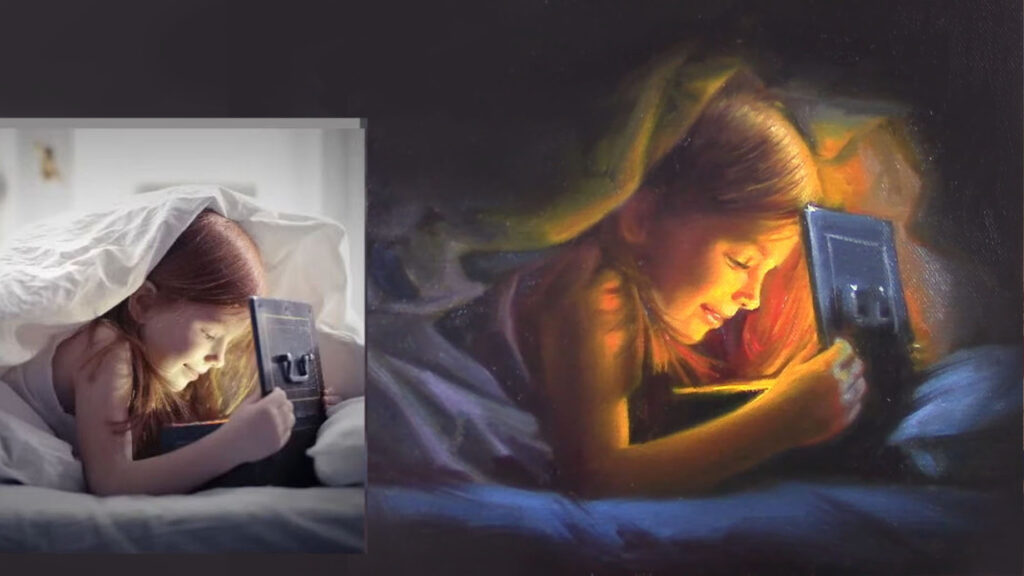

3. Painting What You Want to See (Artistic Intention)

Where Creativity Takes Over

This is where you stylize, exaggerate, or simplify to enhance mood, composition, or emotional impact.

Why It’s Important:

- Makes your work unique rather than just a copy.

- Allows emotional expression—painting a face sadder, more dramatic, or more serene than reality.

- Helps solve compositional problems (e.g., adjusting colors for harmony even if they’re not “accurate”).

Ways to Use It:

- Exaggerate lighting (deeper shadows, brighter highlights).

- Simplify details (merging background elements for focus).

- Shift colors (warmer skin tones, cooler shadows for mood).

- Break realism (intentional brushwork, abstraction).

Examples in Art History:

- Rembrandt deepened shadows for drama.

- Van Gogh swirled skies for emotional intensity.

- Sargent softened edges to guide the viewer’s eye.

How to Balance All Three

- Start with observation—get the basic shapes and values right.

- Apply knowledge—fix anatomical errors, adjust lighting logic.

- Enhance with intention—push colors, soften edges, or emphasize focal points.

Exercise:

- Paint a portrait first strictly from observation, then redo it with intentional changes (warmer/cooler palette, sharper/softer edges). Compare the two!

Final Thought: The Artist’s Choice

Great painters see accurately, understand deeply, and then bend reality to their will. Whether you lean toward realism or expressionism, mastering all three approaches gives you full creative control.

Which do you focus on most—seeing, knowing, or imagining? Try experimenting with the others to expand your artistic range!